That May morning must have been overwhelmingly joyful for 30-year-old Barbara Patton.

Just a year before, the official notifications seemed to just come and come.

The first — in March 1942 — came from the US Navy. Sailor William Anderson Patton, Storekeeper 2nd Class (Sk2) and Barbara’s husband of 10 years, made the “supreme sacrifice” during the first battles of WW2 in The Philippines.

William was dead.

That was soon followed by a letter from Patton’s commanding officer, Capt. Earl Sackett, detailing the manner of William’s death.

Death notifications continued throughout 1942 and into 1943. His name in newspaper lists of Tacoma, Washington’s WW2 dead. Even a mention in Life Magazine‘s July 1942 list of all American WW2 dead to-date.

Reminders, at every turn, to what the young widow had lost.

But then, as these stories often go, Barbara met someone else. A soldier. A younger man. Just 25 years old. He was stationed at Fort Lewis near Tacoma.

The pretty, Tacoma-shipyard typist married Anton L. Holmes on May 14, 1943 — some 15 months after receiving word that William Patton died.

And Barbara and Anton started their life together.

Then, on September 18, 1943 — almost exactly 4 months to the day of their marriage and while Anton was on a training exercise in Oregon — Barbara received another official letter.

But this one was different from the other notifications and letters.

Turns out, the Americans discovered an error: William Anderson Patton was alive. A POW of the Japanese.

Decesions . . . and their consequences

While Barbara was deciding to marry Anton Holmes, her very-much-still-alive husband was making a different kind of decision: Surrender to the enemy and an unknown fate — or — continue hiding from the Japanese and risk execution if discovered.

But to understand the decision Patton faced, we need to back up a bit.

When the Japanese attacked Manila, Philippines, on December 8, 1941 (mere hours after they attacked Pearl Harbor), Sk2 William Anderson Patton had been stationed on the USS Canopus, a submarine tender, for a little over a year. The Canopus supplied food, crew, parts, and other things to American submarines. And, as a storekeeper, Patton’s job was to assist in keeping track of all those supplies.

The Japanese quickly overwhelmed American forces, and on Christmas Eve 1941, the Canopus needed to leave Manila harbor, where it had been anchored since the attacks began.

But the Navy had some warehouses filled with supplies and sub parts they did not want in Japanese hands. So William Patton and 3 other Canopus Storekeepers — Arthur Lazcano, Gordon Fontaine, and John Burk — were ordered to stay and destroy the warehouses while the Canopus sailed away. (Check out Arthur Lazcano’s life sketch for details on this sabotage mission.)

And by the time they completed their mission, the Japanese had overrun the city. They were 4 uninjured, combat-ready American sailors in an enemy-occupied city.

And to avoid being killed on sight, the four men pretended to be civilians.

This is the first decision that would lead to William Patton’s wife getting married to someone else.

Hiding in plain sight

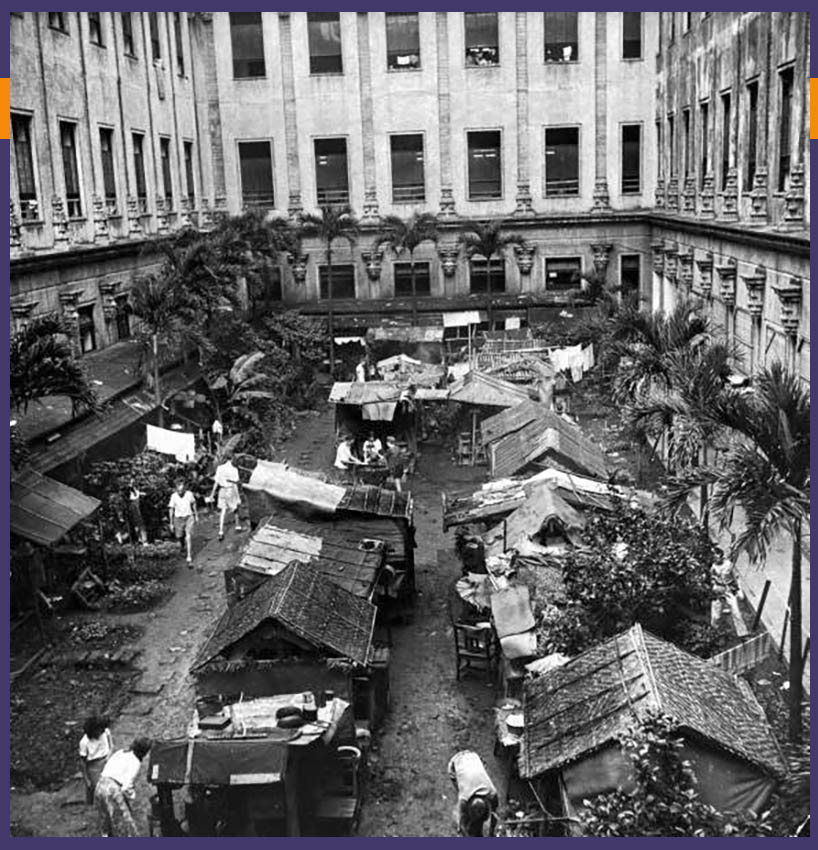

Thousands of American and other “enemy alien” civilians lived in Manila when the Japanese occupied the city on January 2, 1942.

Over the next several weeks, the Japanese transported these civilians to Manila’s University of Santo Tomas, which became a civilian internment camp for the duration of the war. Among the “civilians” who entered Santo Tomas in January 1942 were William Patton and his 3 storekeeper shipmates.

From various records, it seems they used their real names, just omitted the part about being American Navy, and settled into life in camp. That’s why the American military didn’t know about them; they weren’t reported to the Red Cross as military POWs. The American’s assumed all 4 were dead.

For about a year, the foursome hid in the camp — and for details on life in this camp, see Gordon Fontaine’s bio. But then the Japanese heard a rumor: some American military were hiding as civilians in the Santo Tomas camp.

So they issued an ultimatum: surrender now or be found out and executed.

This was the second decision that directly effected Barbara Patton’s marital status and life back home in Washington.

73 days in a Medieval dungeon

“The boys complied,” recalled Alma Salm (who had been their immediate superior officer on the Canopus), “and were immediately thrown into the dungeons at Fort Santiago.”

Fort Santiago, built in 1593, is a fortress in Manila.

During WW2, the Japanese used Ft. Santiago’s dungeons as a prison for some American/Allied POWs, Filipino resistance fighters, and political prisoners.

I’m not certain what qualified an American POW for time in the fort’s dungeons, but I’m guessing it was for the worst “infractions.” See, most POWs in Manila were imprisoned at Bilibid Prison. So Patton and his mates could have easily been sent there. But I’m guessing the Japanese wanted to punish these men for their dishonesty and sent them to Ft. Santiago instead.

The dungeons at Ft. Santiago were crowded and dark. Only faint light filtered in to the stone prisons. The found-out storekeepers received only a small bowl of rice and some water each day.

The fort is on a river and right near Manila Bay, so the ocean tide could affect the dungeons, and some prisoners drowned.

For 73 days in the late spring/early summer of 1943 — the same time that Barbara married and began life with Anton Holmes — William Patton “languished in that dreadful prison enduring the ill-treatment of the Jap guards who watched them night and day,” Salm reported.

The prisoners were not allowed to speak to each other. They had a communal can to defecate in.

After 2.5 months of this torture, the 4 men were transferred to Cabanatuan prison camp, where they reunited with the remaining Canopus crew.

Back home in Washington, Barbara annulled her marriage to Anton Holmes immediately after learning William was alive. The annulment was official in November 1943. (In case your interested, Anton Holmes seems to have remarried in 1945.)

She went on with her life, telling the local newspaper that when William got home, “[we] will take up [our] lives together where [we] left off a couple years ago.”

The dam consequences

While Barbara was adjusting, yet again, to a new life in Washington, William Patton was in the Cabanatuan POW camp in The Philippines.

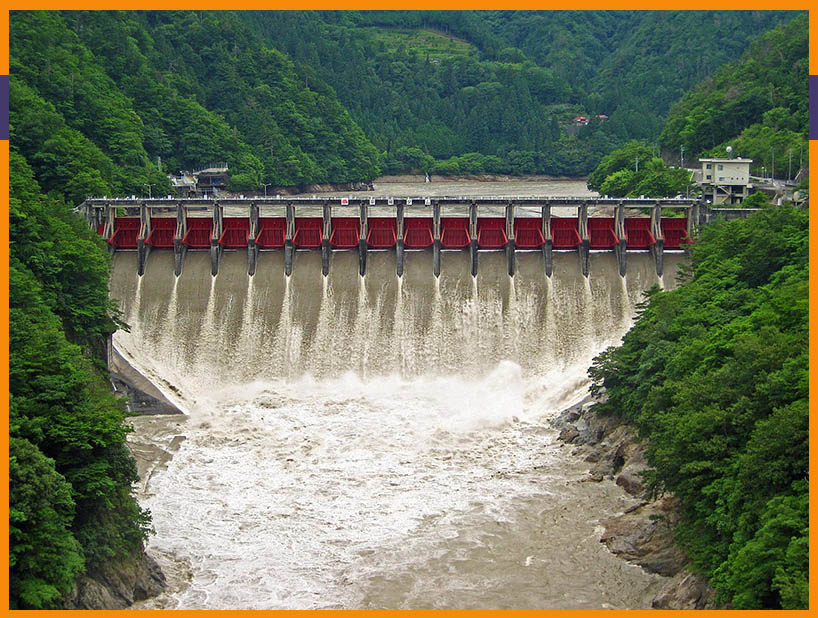

After spending about a year at Cabanatuan, the Japanese transferred Storekeeper Patton to mainland Japan. (He was likely there by August 1944.) He was assigned to the Hiraoka, Nagano, camp, also called Mitsushima. It was part of the Tokyo area POW camps.

This camp was one of the most brutal POW camps, mainly due to the guards who the POWs described as “very severe.” The guards’ treatment of prisoners often seemed arbitrary, and POWs could receive beatings for being uncovered while sleeping or other “infractions.”

Sometimes the men would be forced to stand at attention in the middle of cold winter nights, just for the guards’ amusement.

The POWs nicknamed specific guards The Punk, Scar Face (who beat a POW to death), and Big Bird, among others. 9 Japanese guards were later executed for war crimes against the prisoners.

The camp held around 450 British and American POWs, although thousands of Korean and Chinese slaves were in a separate camp very close by.

The POWs “worked” to build the Hiraoka Hydroelectric Dam. They carried cement, worked in blacksmith and machine shops, and as general laborers.

On September 4, 1945, the Americans liberated Mitsushima; clearing all POWs from the camp by 11:12 am. The liberated prisoners took a train to Japan’s coast, where they met more American military.

After 3 years and 9 months of captivity, William Patton was going home.

Another official notification

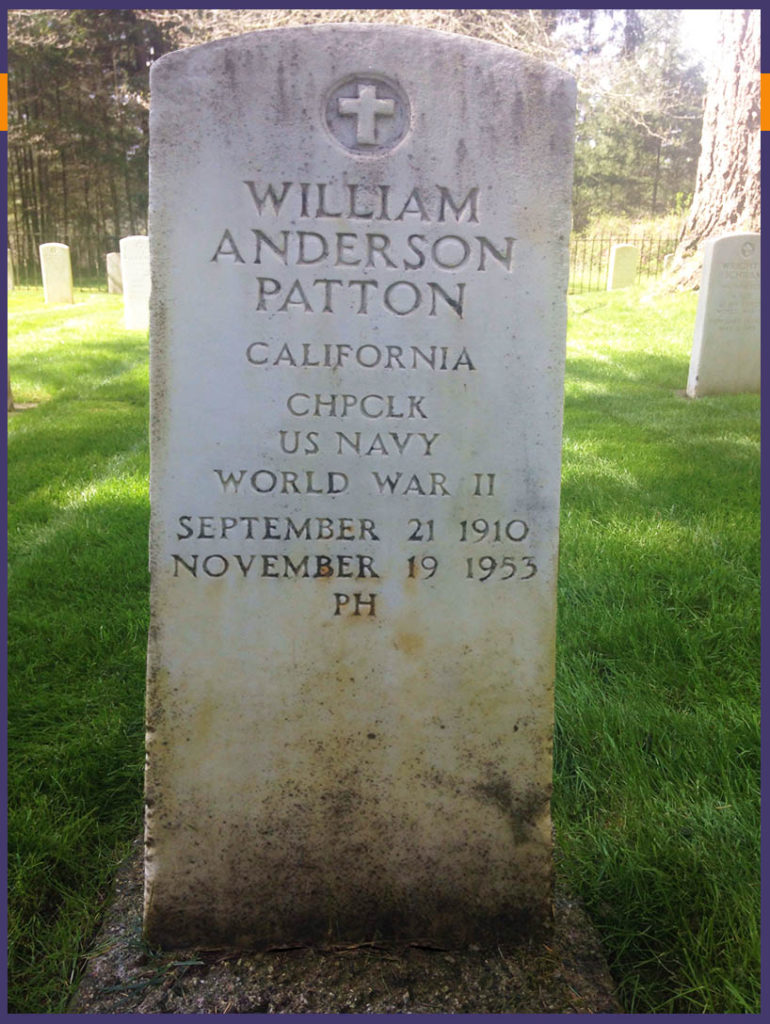

Patton remained in the Navy after the war. In 1949 he and Barbara lived in Oakland, California, and William Patton eventually became a chief pay clerk in the Navy.

On November 19, 1953, Barbara was again living in Tacoma when she received a Navy notification — William died of a heart attack while stationed in Frankfurt, Germany. This time the report of death was accurate. He was 45.

His body was returned to Washington, and he’s buried at Fort Lewis, near Tacoma.

Barbara after William’s death

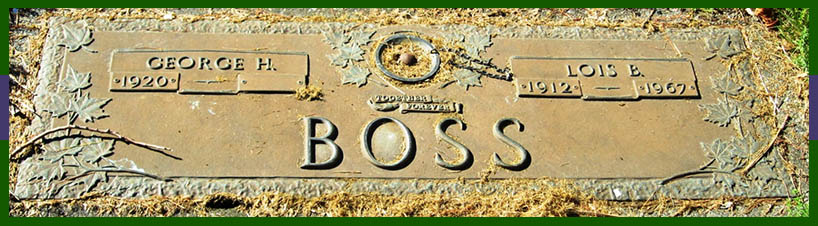

Barbara moved away from Tacoma for good in 1955. At some point she married a man named George Boss and she also started going by her first name Lois. The couple moved to the Los Angeles area and bought a home in Diamond Bar in December 1966.

Just two months later, on Monday morning, February 13, 1967, Barbara was home alone when the house caught on fire. She inhaled smoke, and firefighters found her body at 9:40 am. She was just a few feet from the open front door.

Her body was returned to Tacoma, where she rests in the Calvary Cemetery near her mother.

Final Thoughts

This was a hard story to crack. But after weeks of trying to find out about William and Barbara, I finally found their story.

I wish it had a happier ending. I wish I found pictures of them. But there are surprisingly few documents about either William or Barbara Patton. Which is why researching this story took me so long.

I usually include a small “how to” on each bio, but the one for William and Barbara is too long to include here. So that’s coming soon in another post.

In the mean time, I’d love to know your thoughts on the love story of William and Barbara.

Read Next

Sources

- “Fort Santiago,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Santiago, accessed 30 October 2019.

- “Fort Santiago Photos,” Philippines Travel Guide, found online at http://www.philippines-travel-guide.com/fort-santiago-photos.html, accessed 30 October 2019.

- “Dungeon of Fort Santiago,” Traces of War, found online at https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/90496/Dungeon-of-Fort-Santiago.htm, accessed 30 October 2019.

- “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, entry for Wm Anderson Patton, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Nov 2011.

- “Court Solves Dilemma of 2 Husbands,” Tacoma News Tribune, November 25, 1943, page 8, online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “1920 United States Federal Census,” database online, entry for John A. Maine family, Ancestry.com, accessed 12 November 2019.

- “Asks Court Annul 2nd Marriage,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 28, 1943, page 2, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “California Death Index, 1940-1997,” database online, entry for Lois B Boss, Ancestry.com, accessed 12 November 2019.

- “Casualty List at Center,” Tacoma News Tribune, March 23, 1943, page 9, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “Housewife Perishes in Valley Fire,” Pasadena Independent, Pasadena, California, February 14, 1967, page 15, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 12 November 2019.

- “Fred Olsen,” Seattle Daily Times, July 3, 1949, page 11, found in an Ancestry Member Tree, Ancestry.com, accessed 12 November 2019.

- “Killed in Action,” Life Magazine, July 5, 1943, found online, Google Books, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- Memorial for Constance Beronica “Connie” Olson Wimbles, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13692976/constance-beronica-wimbles, accessed 12 November 2019.

- Memorial for CPO William Anderson Patton, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37087378, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Memorial for Fred K. Olsen, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/164939833, accessed 12 November 2019.

- Memorial for Lois B Boss, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97908974, accessed 12 November 2019.

- Memorial for Mary Lucy Maine Olsen, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9263898/mary-lucy-olson, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “Mrs. George Boss,” Tacoma News Tribune, February 17, 1967, page 7, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- Patton,” Tacoma News Tribune, December 13, 1953, page 53, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “POW Camps in Japan Proper,” POW Research Network Japan, online at http://www.powresearch.jp/en/archive/camplist/index.html#tokyo, accessed 19 November 2011.

- “Remarries, to Learn First Husband, Reported Dead, Is Prisoner of Japs,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 24, 1942, page 1, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “Tacoma, Pierce County War Dead,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 17, 1943, page 1, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “Tacoma, Washington, City Directory, 1954,” in “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” database online, entry for Barbara L Patton, Ancestry.com, accessed 13 October 2019.

- “These Men Gave Lives,” Tacoma News Tribune, July 20, 1942, page 2, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, ca.1775-2006,” database online, entry for William Anderson Patton, Ancestry.com, accessed 12 October 2019.

- “US World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database online, entry for William Anderson Patton, December 31, 1942, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Nov 2011.

- “Washington, Birth Index, 1907-1919,” database online, entry for Louise Barbara Olson, Ancestry.com, accessed 12 November 2019.

- “William Anderson Patton,” Tacoma News Tribune, November 11, 1953, page 2, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 11 November 2019.

- “World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for William Anderson Patton, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 November 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for William Anderson Patton, Ancestry.com, 19 November 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, entry for Wm Anderson Patton, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Nov 2011.

Images

- Image 1. Tacoma, Washington. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 2. USS Canopus. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 3. Santo Tomas Camp. US Army Signal Corps photo, in public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shanties,_STIC.jpg, accessed 3 October 2019.

- Image 4. 1940 pic of Ft. Santiago. Found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fort_Santiago_Intramuros_Manila.jpg, accessed 30 October 2019.

- Image 5. Entrance to Ft Santiago dungeon. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 6. Grates above dungeons. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 7. Map. Created by Anastasia Harman

- Image 8. Hiraoka Dam. Photographed by Qurren, 2007, Wikimedia Commons, online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hiraoka_Dam_free_flow.jpg, accessed 11 November 2019.

- Image 9. William Patton’s grave. Memorial for CPO William Anderson Patton, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37087378, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 10. Memorial for Lois B Boss, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97908974, accessed 12 November 2019.