9 am on March 23, 1942, would have been chilly in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Already officially spring, but temperatures still in the 30s. Clouds covering the sky.

However, the mourners at St. Francis Xavier cathedral probably didn’t pay attention to the weather. They were likely used to it, having already endured the Wisconsin winter.

No, their minds were on a young man — Gordon Fontaine. 21. One of Green Bay’s first casualties of WW2.

A few month’s earlier, Benjamin and Ida Fontaine, Gordon’s parents, got word from The Philippines — their son was missing in action.

But then the official telegram arrived. A telegram every parent dreaded. Storekeeper 2nd Class Fontaine was presumed dead.

So the family held a military requiem mass for their only son. His name appeared in Life Magazine‘s July 5, 1942, issue that listed every American Killed in Action to date. Even his high school’s 1942 yearbook listed his death.

But, you know what they say about presumptions — they make an ass out of . . . No, wait, that’s assumptions. Well, same difference.

Either way, Gordon Fontaine was not dead on that bleak March morning when his parents walked into St. Francis Xavier Cathedral. Far from it.

But the story of why his parents got word of his death, now, that’s a story worth telling.

From Wisconsin boxing to the USS Canopus

Let’s start back at the beginning.

Gordon Raphual Fontaine was born in Green Bay on April 9, 1920. He had 2 sisters (1 older, 1 younger), and his father, Ben, owned a hardware store. Young Gordon attended Cathedral School and then Green Bay’s East High School.

When he was 17 and 18, he competed as an armature boxer. In fact, on February 22, 1938, a 130-something-pound Gordon was knocked out in two rounds by a boxer from nearby Iron River.

And perhaps because his boxing career wasn’t taking off, he joined the Navy in September of that year. Three years later, on September 13, 1941, Storekeeper Fontain joined the crew of the submarine tender USS Canopus.

The ship sailed mainly between China and The Philippines carrying food, fuel, torpedos, supplies, maintenance equipment, and even relief crews for various US submarines.

Stranded: A sabotage mission in Manila

As a Navy Storekeeper, Fontaine helped keep track of supplies. The Canopus had a lot of supplies to track, since it had to supply several submarines as well as its own crew.

When the Japanese attacked The Philippines on December 8, 1941 (just hours after attacking Pearl Harbor), Fontaine was on board the USS Canopus anchored in Manila Bay.

Those early days of war did not go well for the Americans, and within weeks Japanese forces were about to take Manila. The Canopus had to leave. But there were warehouses filled with submarine parts that could not fall into Japanese hands.

So, on Christmas Eve 1941, Gordon Fontaine and 3 other Canopus Storekeepers — William Patton, Arthur Lazcano, John Burk — received orders to “take care of yourselves” and to destroy the warehouses. They stayed behind as the Canopus sailed away. (Check out Arthur Lazcano’s life sketch for details on this sabotage mission.)

They competed their mission, but now the foursome was in a jam. The Japanese had already taken Manila; it was too late to return to the Canopus.

So they reported, as earlier instructed, to officers at the American Naval Hospital in Manila for assistance.

But there was just one, major, problem — the 4 sailors weren’t wounded. And the medical staff, fearing the Japanese would be upset by uninjured, combat-ready servicemen in the hospital, weren’t able to assist them.

Stranded in an enemy-occupied city with no support, there was only one choice left: They pretended to be civilians.

Hiding in plain sight

When Japanese forces occupied Manila on January 2, 1942, thousands of American, British, and other “enemy alien” civilians (ie, not part of the military) called Manila home.

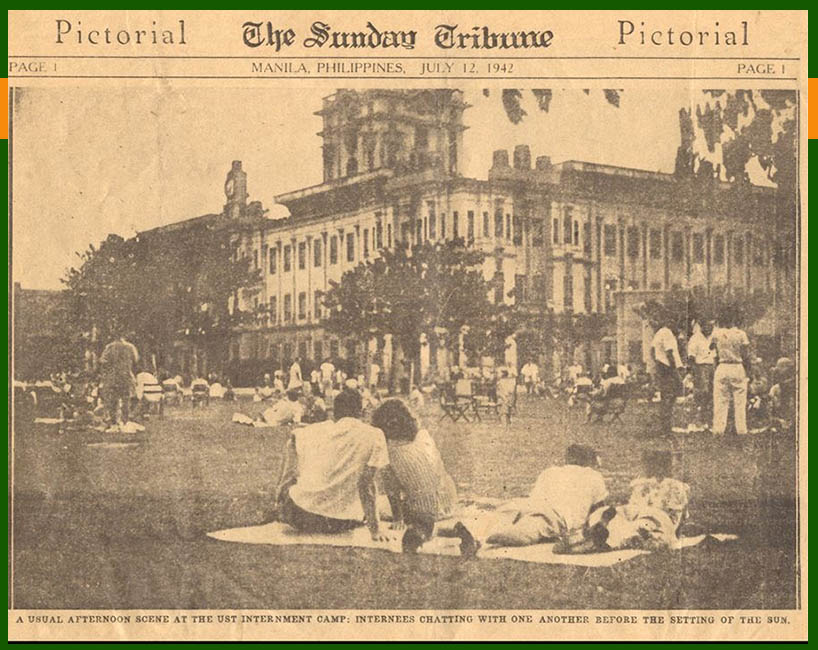

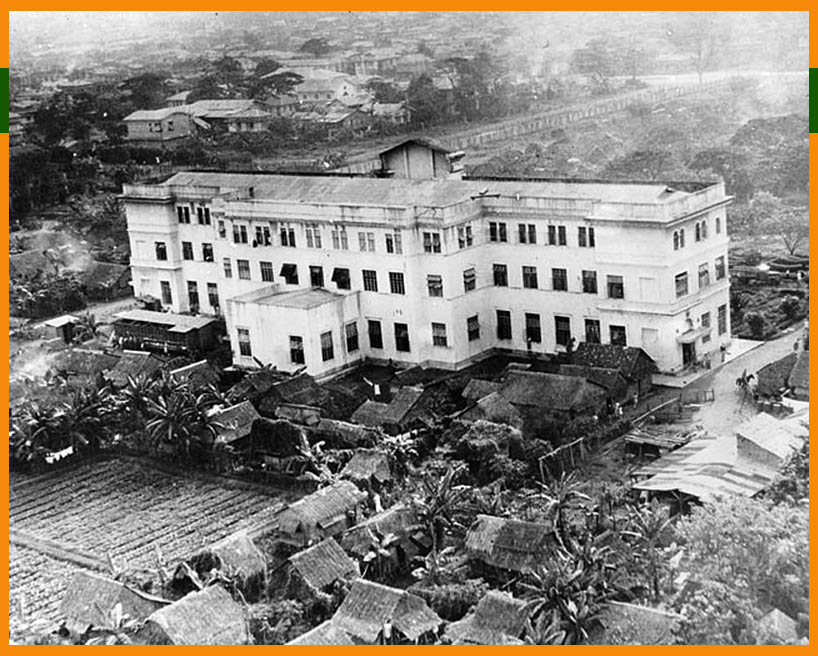

Over the next several weeks, the Japanese began collecting, registering, and transporting “enemy” civilians to Manila’s University of Santo Tomas. The university made an ideal camp because a wall surrounded the entire a 48-acre complex.

So while Fontaine’s parents were mourning his loss on that cold March morning in Green Bay, Storekeeper Fontaine was actually at the Santo Tomas Civilian Internment Camp. He, Burk, Lazcano, and Patton were among the first internees there in January 1942.

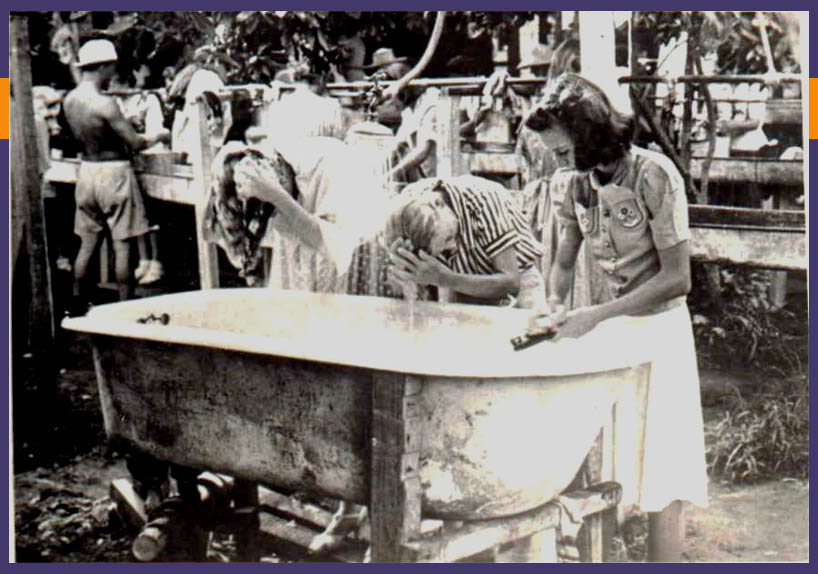

The Japanese propaganda photo above makes the camp seem all afternoon picnics and glorious sunsets. And while the 4 Canopus storekeepers didn’t have to endure the bombardment of Bataan, the siege on Corregidor, or the hellish march to Cabanatuan that their Canopus shipmates did, life at Santo Tomas wasn’t as rosy as the Japanese wanted the world to believe.

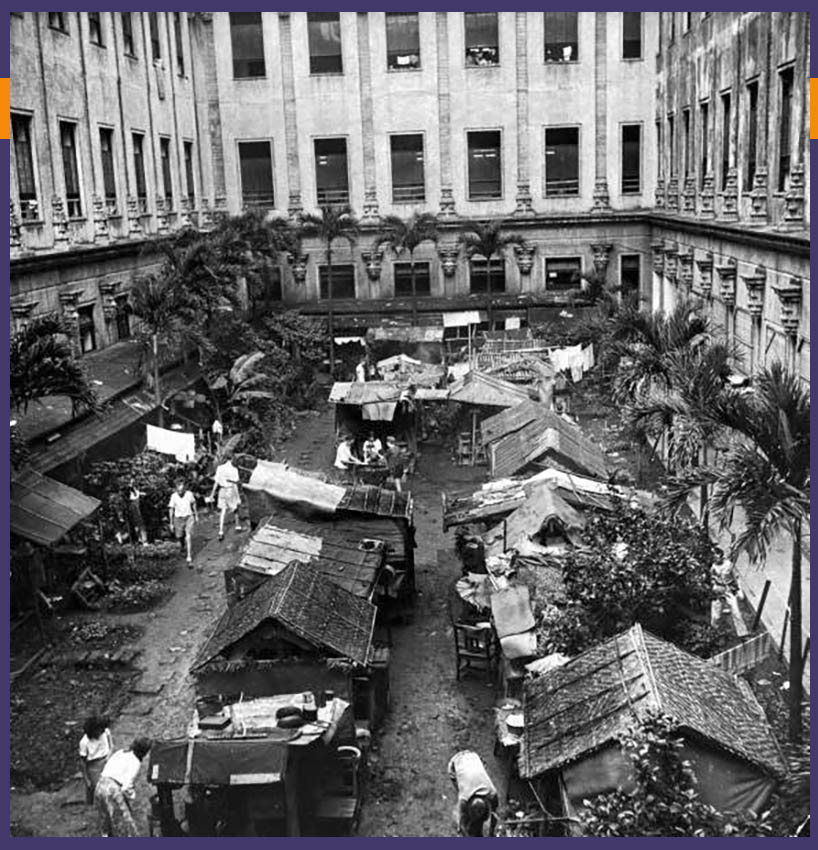

Internees claimed living quarters in classrooms of the various university buildings, which quickly became crowded with 30-50 people per classroom. So “wealthy” internees began building “shanties” on the university grounds.

Internees ran the career and socio-economic gamut — from businessmen to bankers, prostitutes to plantation owners. Some were retired US soldiers who came to The Philippines during the 1890’s Spanish-American War. Others were captured Army and Navy nurses.

Shanties, sanitation, and other camp life

The camp became something of a small city — with its own government and economic system.

For the most part, the Japanese let Santo Tomas internees fend for and govern themselves. The captors provided little food or supplies, so internees took to purchasing items from non-interned Filipinos and growing their own food.

Still, a class system developed with in camp. Those who had money could buy food and eat. Destitute internees often went without — especially as supplies decreased and prices rose in camp. Internees with money could buy materials to build bamboo-and-palm-frond shanties. They became a sort of “camp aristocracy.”

The internees set up a camp government, a police force, and a hospital. The camp’s Sanitation and Health Committee boasted more then 600 internee workers who built facilities for toilets, showering, dishwashing, and cooking. They took care of garbage and pest control.

But food and sanitation would remain the biggest issues for camp residents. 1,200 people shared 13 toilets and 12 showers. Long lines became standard for toilets and food. And the camp government — faced with internees who did not have money to buy food — began providing morning and evening meals.

The internees were segregated by gender. And the Japanese tried to ban affectionate and other relations between men and women. Their efforts were met with varying degrees of success. After all, if you had a private shanty . . .

The sailors are found out

For more than a year, Gordon Fontaine and his shipmates enjoyed bearable conditions at Santo Tomas.

Disease and malnutrition — which plagued other POW camps in The Philippines — were not as big of problems at Santo Tomas, at least during that first year.

Few Japanese guarded this camp, and internees enjoyed freedoms that military POWs did not. Internees had to be present for nightly roll call at 7:30 pm. The few who attempted escape were beaten, tortured, and executed, as in other POW camps.

And then, in late spring 1943, the Japanese learned something . . .

Several American military personnel — such as Fontaine, Burk, Patton, and Lazcano — were hiding in Santo Tomas. The Japanese “issued a stern warning”: identify yourselves at once or face execution if you’re found out later.

What would you do? Surrender to a unknown punishment or continue hiding?

Gordon Fontaine and his 3 shipmates gave themselves up. Instead of execution, they spent 73 days in a dungeon before being transferred to the main Philippine POW camp (called Cabanatuan) in summer 1943. (Get details of their dungeon experience in Patton’s bio and their Cabanatuan experiences in John Burk’s bio.)

“The worst experience of all”: Fukuoka’s Pine Tree Camp

At some point, I haven’t discovered exactly when, the Japanese sent Storekeeper Gordon Fontaine from The Philippines to a POW camp in Japan — Fukuoka #1, which the prisoners called the “Pine Tree Camp.” It was a camp one POW described as “without question, excepting the hell ships, the worst experience of all.”

And where heat and humidity had been the norm in The Philippines, the weather was vastly different at the Pine Tree Camp. Especially during the winter.

Fontaine and his fellow POWs lived in barracks with dirt floors, where they slept on raised wooden platforms. Their diet was mainly rice, with some vegetables and vary rarely meat.

Enlisted men, like Fontaine, did manual labor, such as digging tunnels in nearby hills and working at the nearby airport. It was heavy work that their diet didn’t offer near enough energy and strength to perform.

The guards were not sympathetic to sick men, making them continue working, cutting their rations, and hitting and kicking them when they didn’t keep up. The camp had a “hospital” staffed by captured Allied doctors, but they had little medicine to help sick and wounded men.

The camp commander was a brutal man, as were his guards, 2 of whom the POWs nicknamed “Bulldog” and “The Beast” because of their brutal beatings. The prisoners endured constant roll calls, inspections, and punishment for minor “crimes.”

In September 1945, some 3 years and 9 months after his capture in Manila, Gordon Fontaine was liberated from the Pine Tree Camp.

After the war

About 10 months later, in July 1946, Gordon married Virginia Posik in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

He stayed in the Navy for another 15 years, becoming a Chief Warrant Officer in July 1953. The Fontaine family was stationed in various locations in the US during Gordon’s military career.

After retiring from the Navy, Gordon moved his family — now consisting of a wife, two daughters, and one son — back to Green Bay. He worked for the school board until retiring in 1978.

66-year-old Gordon Fontaine died on October 20, 1986.

Today he has 2 living daughters, 4 grandchildren, and at least 2 great-grandchildren.

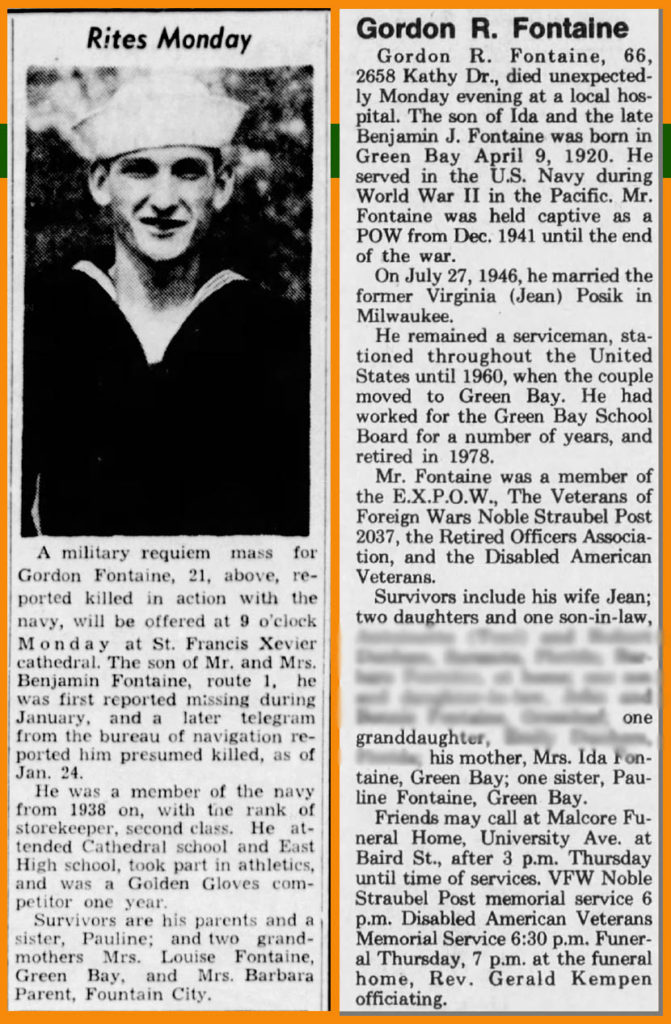

It’s all about the obits

Obituaries, or “obits” as they’re called in the biz, are kind of morbid gold mines.

Obits are death notices that appear in newspapers. What makes them so great is that they often include:

- Pictures of the deceased person

- Info about birth, marriage, and death

- Names of family members — both living and passed on (especially names of parents, siblings, spouses, and children)

- Life details such as occupation, organizations belonged to, and honors recieved

- Stories about the person’s life

These details can be especially useful when you’re trying to learn more about a family member who died roughly between 1970 and today, because most of the records (birth, marriage, death, census, military) that we rely on to create a family tree aren’t often publicly available for that time period. But, as you can see from the list above, an obit can provide some of those details.

Here’s the 2 obits for Gordon Fontaine. The one of the left is the “wrong one” from March 1942; on the right is the real one from 1986. Notice all the info these 2 short articles give about him and his life. Priceless!

There are so many places to find obits — both modern and historic.

A lot are online at many local newspapers’ websites. Tip: Scroll to the bottom of the home page and look for the word “Obituary.”

I mainly use Newspapers.com, which is a subscription website with a lot of historic newspapers. You can also find historic newspapers on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. Many libraries have microfilm or digital versions of local newspapers.

So the next time you’re trying to find a story in your family tree, try searching for an obituary. I’m pretty certain you’ll strike family history gold!

Read Next

Help us honor Fontaine

My main goal is to help us all honor and remember the men and women who spent years as POWs of the Japanese. You can help me accomplish that by sharing this list sketch with friends dna family.

Sources

- “1930 US Federal Census,” database online, entry for Gordon Fontaine,” Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- Colonel Wibb E. Cooper, Medical Corps, Medical Department Activities in The Philippines from 1941-6 May 1942 and Including Medical Activities Japanese Prisoner of War Camps,” written April 1946, found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/Page04.htm#Goodpasture, accessed 10 July 2019.

- “Gordon R. Fontaine,” in The Quan newsletter, November 1986, page 6, online at http://philippine-defenders.lib.wv.us/QuanNews/quan1900s/quan1980s/november_1986_quan.pdf, accessed 23 October 2011.

- Harold K. Johnson, affidavit on experience as a POW, found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/USAffJ-P.htm, accessed 10 July 2019.

- “Hans Alh, Oshkosh, Wins Boxing Title,” Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, 23 February 1938, page 13, newspaper online, World Vital Records, accessed 23 October 2011. “Killed in Action,” Life Magazine, July 5, 1943, page 38, online, Google Books, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “Killed in Action,” Life Magazine, July 5, 1943, page 38, online, Google Books, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- Obituary for Virginia Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 6 Jan 2019, Page A10, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

- Obituary for John Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 16 Jan 2014, Page A11, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

- Obituary for Gordon R. Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 22 October 1986, Page 23, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

- “Prisoner of Japs,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, 23 December 1942, page 10, online, NewspaperArchive.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “Rites Monday,” Green Bay Post-Gazette, Green Bay, Wisconsin, March 18, 1948, page 5, online at Newspapers.com, accessed 2 October 2019.

- “Santo Tomas Internment Camp,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santo_Tomas_Internment_Camp, accessed 3 October 2019.

- “Social Security Death Index,” database online, entry for Gordon Fontaine, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “US World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database online, entry for Gordon R, Fontaine, 31 March 1942, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, entry for Gordon Raphual Fontaine, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for Gordon Raphual Fontaine, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

Images

- Image 1. St Franics Xavier Cathedral. Courtesy Ken Lund, posted to Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/kenlund/9181858116, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 2. Gordon Fontaine picture. “Rites Monday,” Green Bay Post-Gazette, Green Bay, Wisconsin, March 18, 1948, page 5, online at Newspapers.com, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 3. USS Canopus with submarines. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 4. Manila Pier 7. Posted online by John Tewell, flickr, https://flickr.com/photos/johntewell/6986754105/in/album-72157623238815677/, accessed 27 September 2019.

- Image 5. Santo Tomas propaganda photo. From The Sunday Tribune, July 12, 1942, page 1, Manila, Philippines, found online at http://arquitecturamanila.blogspot.com/2014/07/university-of-santo-tomas-main-building.html, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 6. Santo Tomas Internment Camp. US Army photo, public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santo_Tomas.jpg, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 7. Aerial of Santo Tomas main building. Manila Nostalgia/Mon Ancheta, found online at http://arquitecturamanila.blogspot.com/2014/07/university-of-santo-tomas-main-building.html, accessed 3 October 2019.

- Image 8. Shanty courtyard. US Army Signal Corps photo, in public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shanties,_STIC.jpg, accessed 3 October 2019.

- Image 9. Women at Santo Tomas. US Army Signal Corps photo, in public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WomenPOWs2.jpg, accessed 3 October 2019.

- Image 10. Map. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 11. Pine Tree Camp. “Prisoner of War Camp #1: Fukuoka, Japan,” found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/Page01.htm#Locations, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 12A. Virginia Fontaine photo. Obituary for Virginia Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 6 Jan 2019, Page A10, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

- Image 12B. John Fontaine photo. Obituary for John Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 16 Jan 2014, Page A11, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

- Image 13A. “Rites Monday,” Green Bay Post-Gazette, Green Bay, Wisconsin, March 18, 1948, page 5, online at Newspapers.com, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 13B. Obituary for Gordon R. Fontaine, Green Bay Press-Gazette, 22 October 1986, Page 23, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 28 October 2019.

So interesting!!!!! Thank you! An amazing time with amazing lives lived!