This post is part 9 of Alma Salm’s memoir of being a POW in The Philippines during WW2. You can read from the beginning here. Also, this post contains some mildly graphic descriptions of war-time treatment of POWs.

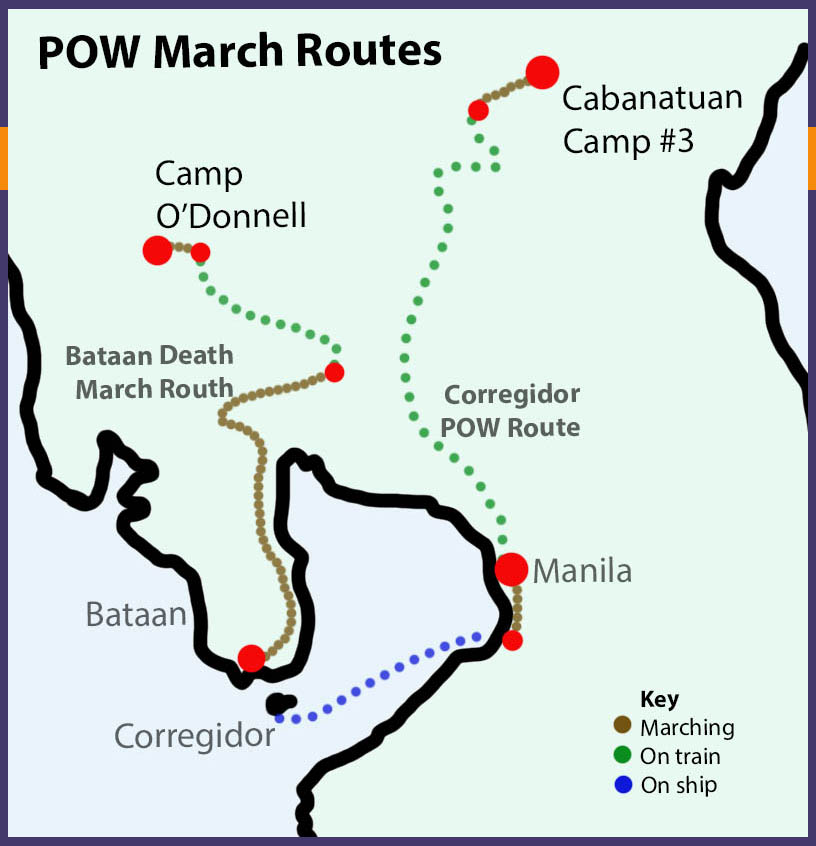

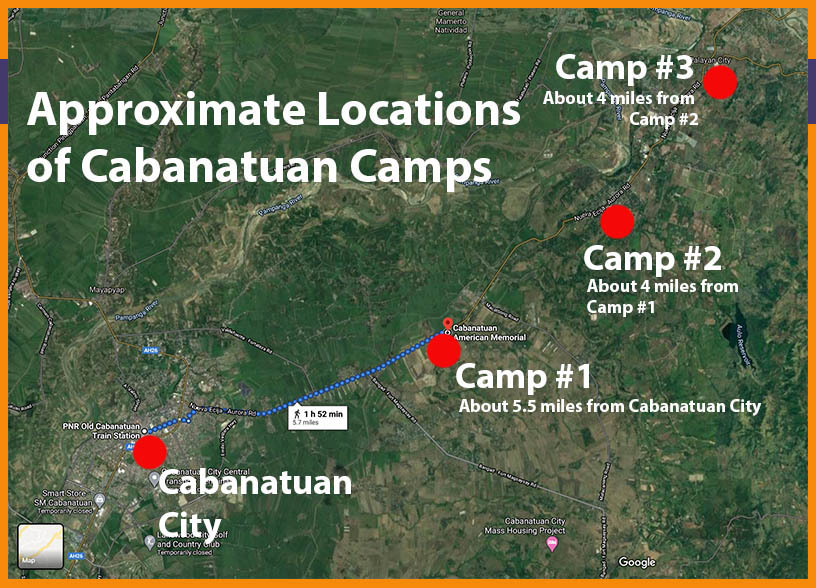

About three o’clock on May 27, 1942, a tired dusty column of POWs marched up to Cabanatuan Prison Camp #3.

It was headed by “Soochow,” panting heavily. The moisture dripping from his lolling tongue told plainly that even in a dog’s life [the march] had indeed been a hot, laborious journey.

Pet friendly (or at least tolerant)

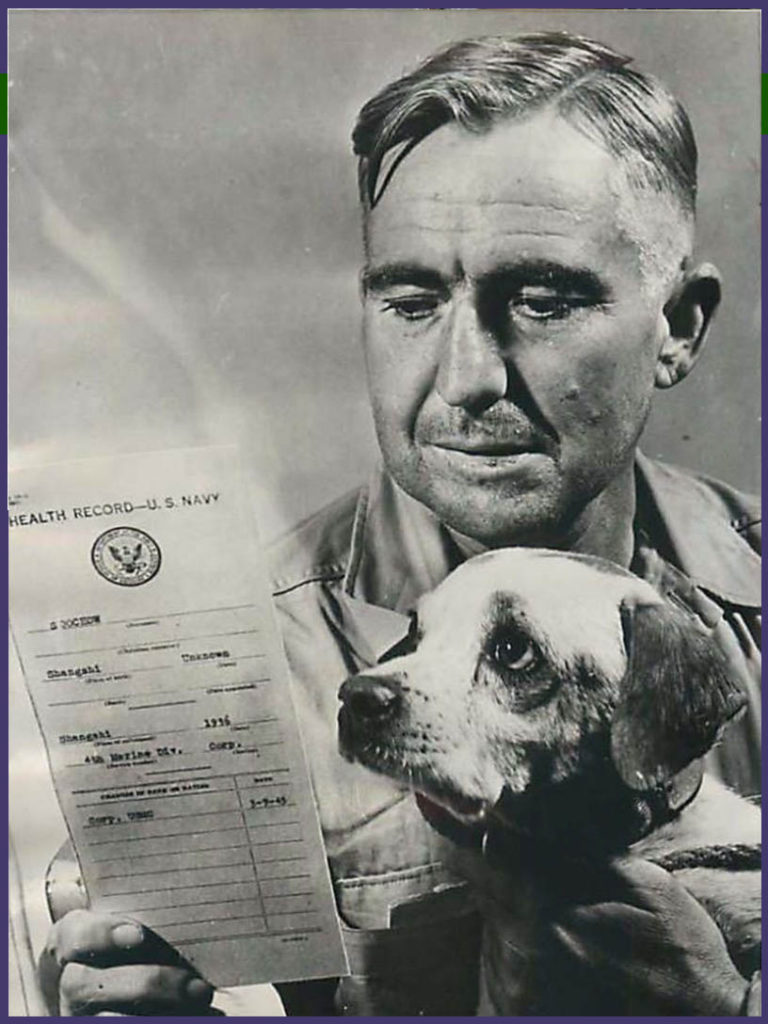

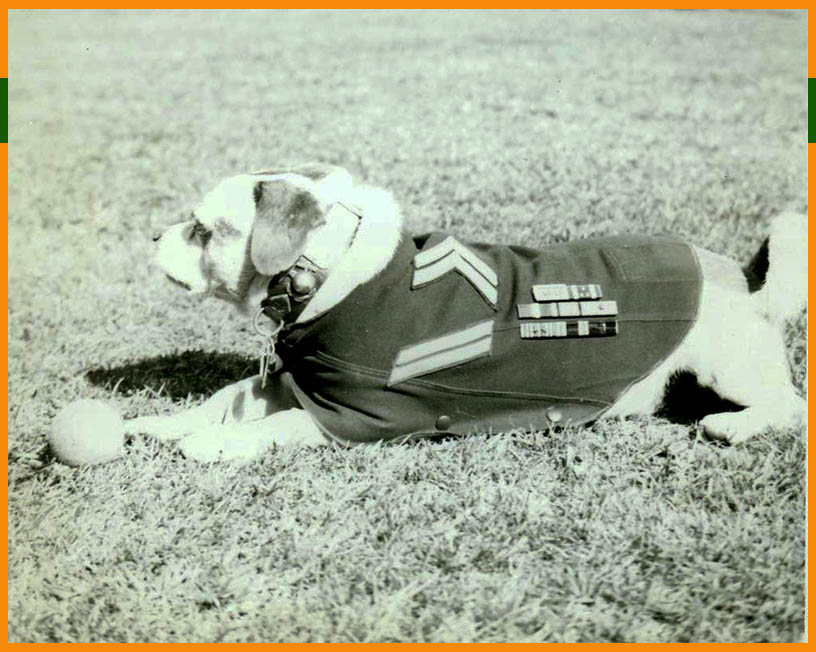

Soochow was a Chinese dog and mascot of the U.S. Fourth Marines in Shanghai, China. He went thru the campaigns with the “Leathernecks” [nickname for Marines], and on into [Cabanatuan] Prison Camps Number Three and One, and finally left us with a detail for Fort McKinley in November 1944.

He was a friendly little brown and white canine — with large, rather protruding sad brown eyes and head like a large Pekingese. His hair was straight and short.

Soochow tolerantly took his share of our burdensome life at this prison camp. He ate rice, lapped up his share of our “green death,” suffering the “back door trots” as a consequence, and all the other discomforts with the rest of us. He was covered himself periodically with sores and scabby back, recovered after long periods, and carried on a battle scarred as any veteran.

I used to wonder why the Japs in one of their strange intolerant moods did not order him done away with.

A warm camp welcome

Before we were permitted to enter our respective habitats [at Cabanatuan Prison Camp #3], we had to spread out before us on the ground all personal belongings. This was closely examined by the Japanese Military authorities of this camp. Word swept through the camp like wild fire to hastily get rid of any Japanese peso currency.

At Camp O’Donnell, a short time before, a similar search had taken place with those incarcerated there who had made the infamous “Death March of Bataan,” and all those found with Jap currency on their persons were taken “over the hill” and presumably executed, as they were never seen again.

The Nipponese concluded that, up to this time, the only way we could come in possession of Japanese pesos would be by robbing some dead Nip soldier on Bataan or Corregidor. To them this was a defilement of their dead — and such a deed called for the death penalty.

Within the next four days three thousand more military prisoners arrived [at Camp #3] , which raised the camp population here to slightly over six thousand officers and men of the various United States Military and Naval services. Thereafter, the balance that remained in Bilibid [POW Camp in Manila], except hospitalized personnel, were sent to the Cabanatuan Military Prison Camp Number One.

Non-combatant civilian personnel in Manila when war broke were interned in the civilian internment camps at Santo Tomas, Manila, and some later at Los Banos, Rizal Province, about thirty kilometres from Manila. The military prisoners were never interned with nor saw the civilian internees during the entire period we were under the heel of the sons of Nippon.

Rustic, spacious accommodations

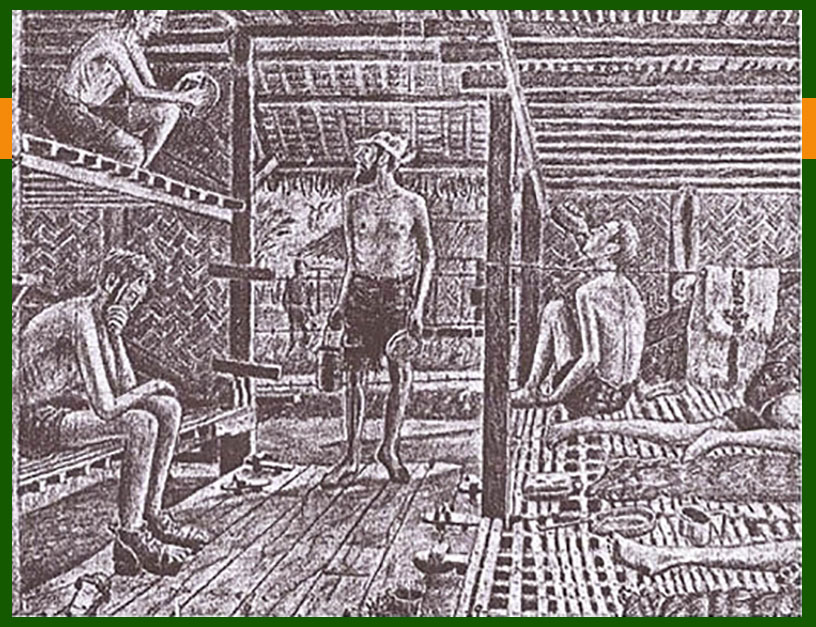

We were assigned to various buildings [at Camp #3]. Most of these dwellings, which had previously been built to house the Filipino Army, then in training, were similar to Filipino nip huts or bahay except these habitats were larger. They consisted of thatched roofs and swali (woven mat from split fiber of rattan or similar flexible stems) sides. The structures were elevated two feet above the ground on stilt-like timbers.

There was a door at each end of the building in the center and a pathway ran thru. About twenty or thirty inches above the bare ground was a frame work on which were laid long bamboo strips about one inch wide with a two inch open space between them and which ran shelf-like the entire length of the bahay on each side of the center path. This shelf-like arrangement is know as a benig (bed frame).

About five feet above this lower benig was a second deck or loft of similar parallel construction which, of course, did not allow sufficient height in between the two for a normally built man to stand upright, so one was obligated to crawl in and out of the lower benig. High above the the second shelf directly over the center path was another similarly built section about five feet wide running the full length, referred to locally as the “catwalk.”

These spaces were our homes and beds. About one hundred and thirty-five men were compressed into one of these forty-foot buildings, which normally housed forty Filipino soldiers.

Here we lay on the bamboo slats shoulder to shoulder in rows. There was positively nothing else in the barracks. No bedding or wearing apparel was issued to us by the Japs. If you possessed a blanket you had a blanket to lie on — if you didn’t you just slept on the plain bamboo strips. They ran at right angles to the position of your body and felt like small boulders or rocks under you in places because of the uneven curvature of the split bamboo stems.

And so began “our life under the Japanese Flag.”

Meet the camp crew

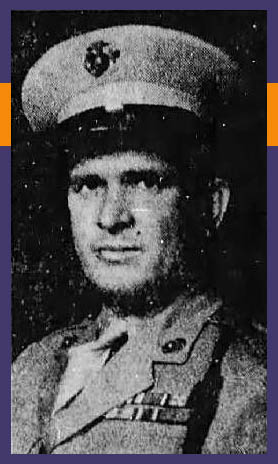

Colonel Napoleon Budreau, Coast Artillery, U.S. Army, was our amiable American camp commander and Lieutenant Colonel Curtis Beecher, U.S. Marine Corps, was his able adjutant. Colonel “Napoleon” as he was called by the Japs, was a fine understanding officer, and we were all sorry when he was transferred to Bilibid Prison [in August 1942].

Our officers were required to see that all Jap orders and regulations were carried out. They had no authority of their own. Lt. Colonel Mori, Imperial Japanese Army, was our Japanese camp commander.

The only distinction made between officers and men was that they occupied different barracks, but both barracks were furnished identically — with nothing. The officers’ barracks were alongside those of the men. In accommodations, food, or treatment, a Lieutenant Colonel and a private were accorded the same by the Japs.

All-inclusive — and the extras

However, there were a considerable number of exceptions among officers and men both who possessed funds of their own at this late date and were thereby able to augment their scanty Jap-issued rations by purchases thru a sort of commissary which was later established.

Comparatively few, however, were fortified to an appreciable extent with sufficient funds to do much good for long. Most of the men had little or no funds at all.

For the most part those able to procure this additional food were free from the diseases which ravaged the camp.

We were not much better off than a herd of cattle in a barb-wire enclosure. It is true we had the barren bahays, except for the few personal belongings stowed therein, which provided shelter from rain and sun and to lay our always tired bodies on the bamboo battings. Not a chair nor a table was available yet. We drew our ration and sat on the benig in our bahay or outside on the ground to consume it.

Our bachelor establishment boasted no facilities or conveniences. A most primitive type of existence prevailed, and, judged by the standard living of the plebeian Japanese, we had descended considerably.

On-site private chefs

No containers of any kind from which to eat our dirty, maggot-infested rice was given to us. Had not most of us had our mess kits, canteens, and canteen cups attached to our person when we came in, we’d have indeed been back to 5,000 B.C. Unfortunates had to fashion a plate of sorts from any old piece of salvaged tin or galvanized iron lying about.

Our kitchen was a large open-sided shed with thatched roof.

Here were a series of holes dug in a row in the ground to accommodate the iron rice pots with a short dug trench leading to them in which to feed the fire underneath. Some old galvanized iron was located and fashioned into a short chimney and placed in back of the pot to carry away the smoke of the wood fires and to also provide a flue for draft.

The cast-iron rice pots were a blunt, round-shaped utensil about twenty-four to thirty-six inches in diameter, and about fourteen to sixteen inches deep in the center. These were set into the concavity in the ground. Here our rice was cooked by our own men who, at the beginning, knew very little about cooking rice under these conditions.

Fuel up on greens

In some of the pots, greens were boiled. These consisted mostly of a succulent swamp vine, the stems of which were tubular and which the men dubbed “whistle weeds.” Occasionally some squash or native eggplant was furnished in small quantities, which were cut into small pieces and boiled with these “greens.” However, such small amounts were added to the soupy concoction, it was hardly noticeable.

The cooked rice and soup was placed into five-gallon oil and gasoline tins and each barracks strictly issued the number of rations allowed for that barracks.

The soup was unpalatable most of the time, and when camote (native sweet potato similar to American yams) vines were added, it was almost bitter. Although digestible it was responsible on many occasions for men having the “runs.”

Exclusive rice recipes

The rice, in the early days of our imprisonment before the men were adept, was cooked to a thick gelatinous-like substance. This was, for the most part, our daily diet. At times, in attempting to make the rice more palatable, a process was tempted to steam it, but frequently it wasn’t fully cooked, and the raw, uncooked starch gave us gas and stomach aches and also the “runs.”

After one of these unpalatable treats followed by the usual unpleasant reaction, I overheard one of our cooks mumble to various and sundry, “Hell! we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t.” He didn’t get any farther in his tirade for on the next instant he was making toward the latrine on the double with a string of unprintable epithets trailing behind.

Even the cooks were driven to eating their own “poisonous” concoctions and accepting their fate with the rest of us.

Diet trends to die for

The cans containing our food were placed on the ground in front of each barracks, and, after making futile attempts to brush away hundreds of large, red-headed blue-bottle flies, the men would line up and each receive a ration of rice and a small ration of soup. The quantity was about three-quarters of a level old-style army mess kit and about one-half canteen cup of the “green death,” as the soup came to be called.

This diet improperly cooked in the beginning plus the total lack of so many food essential to the well-being of the human system, caused gradual change in the body chemistry as well as many gastronomical disturbances. It was the beginning of the type of diet which continued so long and was responsible for so many deficiency diseases. And eventually was the proximate cause of so many hundreds of deaths due to malnutrition and malnutritious diseases, or due to lack of proper foods to fortify our men with resistance and strength.

This brought about the deaths of other hundreds of our officers and men from bacillary and amoebic dysentery.

Bacillary dysentery: Causes diarrhea with belly cramps, fever, nausea and vomiting, blood or mucus in the diarrhea. Transmission is fecal-oral and was largely spread by flies landing in feces and then on the POWs food.

Amoebic dysentery: Causes abdominal pain, diarrhea, or bloody diarrhea. Severe cases can lead to colon ulcers, anemia from blood loss, and liver abscesses. Often caused by poor sanitation, especially in handling of food and water.

Close ups with native wildlife

The spread of diarrhea and dysentery was rampant, and, being endemic, it soon became epidemic due to the insanitary conditions under which we lived. The blue-bottle flies, or “blow flies,” helped spread the disease.

Camp sanitation was very poor or practically non-existent. The open latrines were ideal for the breeding by the millions of these pests. The flies were “black messengers of death,” causing the spreading of the dreaded dysentery throughout the camp.

They were particularly attracted by anything that fermented or soured. Sometimes where the waste water from rice washings would stand and sour in small drainage ditches, they would be black around the banks. It was an ideal breeding place too.

Undaunted they would make a landing right on top of your rice ration while eating, and you had to almost brush them off forcibly at times.

Excursions to socialize with locals

We learned the agony of war and now as prisoners we were to learn the agony of “peace” in a Jap military prison camp.

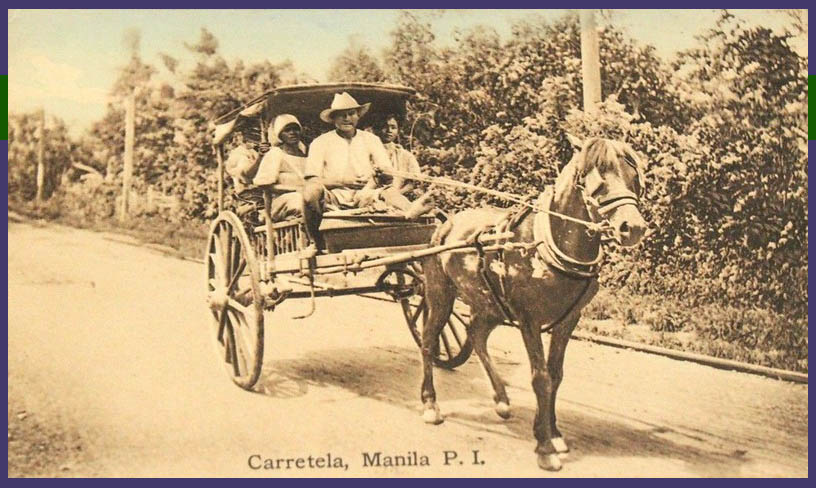

Each day we were sent out of camp on work details. It wasn’t long before itinerant Filipino vendors, learning of our whereabouts out on the detail, would line up on the road nearby displaying their wares in front of their carromatas (two-wheeled covered vehicle). These consisted of cooked native food, mangoes, canned fish, milk. bananas, cigarettes, native candy, and sometimes fried chicken.

We had to depend upon the temperament of the Jap guard in buying. Some overly suspicious would not permit our coming in contact with the Filipino. Other guards would say “O.K.” for maybe ten minutes.

Let me tell you! When that okay was given a football skirmish was child’s play.

For the first few days, we were permitted to take our purchases back into camp. Then an order was issued by the Jap Camp Commander strictly forbidding such consideration. He decided we were loosing too much valuable time away from our work by these purchases.

However, despite this, an occasional guard a little more humane, would give us fifteen minutes to buy and eat our purchases out there on the spot but admonished to cart none into camp. We, therefore, began secreting a little that wouldn’t bulge too much about our person: under our hat, tied to our leg, under our crotch. I utilized my water canteen into which I poured two small bottles of ketchup with hopes of disguising the tasteless rice and “green death.”

This also came to an end very abruptly by our perplexing overseers. The Filipino vendors were suddenly chased from our work detail vicinity and as further check we were all searched on return at the camp gate.

Many a poor devil was beaten for disregarding this law.

Read Next

Sources

- Eric Niderost, “A Memorable Marine Mascot,” Warfare History Network, found online at https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2016/07/14/a-memorable-marine-mascot/, accessed 28 April 2020.

- “Camp O’Donnell and Camp Cabanatuan,” Mansell.com, information from Colonel Irvin Alexander, author of Surviving Bataan and Beyond, published from his manuscripts made in 1949, found online at http://www.mansell.com/lindavdahl/omuta17/odonnell_cabanatuan.html, accessed 28 April 2020.

- “Historical Report, U.S. Casualties and Burials at Cabanatuan POW Camp #1,” Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Washington, DC, found online at https://www.dpaa.mil/Portals/85/Documents/Reports/U.S.Casualties_Burials_Cabanatuan_POWCamp1.pdf?ver=2017-05-08-162357-013, accessed 28 April 2020.

- Office of the Provost Marshal General, “Report on American Prisoners of War Interned by the Japanese in The Philippines,” 19 November 1945, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/pows_in_pi-OPMG_report.html#Camp_One, accessed 29 April 2020.

Images

- Image 1. Soochow and Sergeant Paul Wells, ca 1946, found online at https://www.auctiva.com/hostedimages/showimage.aspx?gid=11427&ppid=1122&image=942176133&images=942176119,942176133&formats=0,0&format=0, accessed 28 April 2020.

- Image 2. Soochow in uniform, ca 1964, official USMC photograph, From the Donald W. Curtis Collection (COLL/3238), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/usmcarchives/18517234130/in/photostream/, accessed 28 April 2020.

- Image 3. Map of POW marches. Created by Anastasia Harman, April 2020.

- Image 4. Approx. locations of Cabanatuan POW camps. Created by Anastasia Harman from Google Earth satellite image, April 2020.

- Image 5. POW Barracks at Cabantuan. Prison Hut at Cabanatuan POW Camp. US Army photo, public domain, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raid_at_Cabanatuan#/media/File:Cabanatuan_Prison_Hut.jpg, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 6. Barracks interior. “Life and Death at Cabantuan POW Camp,” Yank Magazine, 1944, OldMagazineArticles.com, found online at http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/GREAT-RAID_CABANATUAN_PRISON_CAMP-ARTICLE, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 7. Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher. Memorial for BG Curtis T. Beecher, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62816897/curtis-t_-beecher, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 8. Mess kit. 1944 Original USA Issued WWII Soldiers Mess Kit Including Canteen, Spoon, Fork, Knife, uploaded by Kevin Bartle, Rock and Rhino, found online at https://www.etsy.com/listing/528880083/1944-original-usa-issued-wwii-soldiers?show_sold_out_detail=1&ref=anchored_listing, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 9. Succulent plant. Crassula ovata, Annie’s Annuals and Perennials, found online at https://www.anniesannuals.com/plants/view/?id=4674, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 10. Blow fly. “Blow fly,” Encyclopedia Britannica, found online at https://www.britannica.com/animal/blow-fly-insect, accessed 29 April 2020.

- Image 11. Carretela. Carretela, Manila, P.I., ca 1900, courtesy Eduardo De Leon, Flikr, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/edlei/24201979426/in/album-72157656355214903/, accessed 29 April 2020.

![A Brutally Honest Look Inside Japan’s Largest WW2-era POW Camp [Memoir #9]](https://www.anastasiaharman.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Memoir-9-Cabantuan-intro-367x780.jpg)

Enjoyed the read. So many facts I was unaware of. Thank you.

I’m so glad to hear that! Thank you for taking time to read it 🙂

MY GRANDFATHER WAS BENJAMIN ANDREW RUSH. WHAT DO YOU HAVE ON HIM??

I emailed your sister yesterday. 🙂 Hopefully some of the info will help you know more about your grandfather’s time as a POW!

I’m organizing my father’s scattered memoirs and his journey from Shanghai (Fourth Marine Band) to Corregidor to Cabanatuan to working in the mines in Japan. To explain and verify this compilation, I ordered 6 books in addition to what I looked for online. But none of them helped me make sense of his references to Camp #1 and Camp #3 until I stumbled, quite accidentally, on this site. Thank you so much for posting this and their history. I am in your debt. SO HELPFUL!

I am SO glad it was helpful. Figuring out Cabanatuan Camps 1,2, and 3 took me a while, but it was so helpful once I did figure out where they were and what they were used for.