Luzon Holiday manuscript pages 6-14. This post contains some mild swearing.

Disjointed conversation drew my attention to the sorry comrades-in-arms about me.

Soldiers, sailors and marines — all intergrated into one land-fighting force — battle stained and weary — stood in various attitudes of helpless waiting and speculation. Some men silent, gaunt-eyed with strain-telling expressions stared seaward as though still hopeful of the promised help from beyond the horizon. Others gave way to muttering their disillusionment and disappointment at being in such a state of helplessness; of uncertainty.

Dejection and bedtime stories

One pessimistic Army Sergeant disgustedly voiced his views as he periodically expectorated through three freshly broken front teeth. “Hell! They send us out here equipped like little boys with a few down-at-the-heel popguns — expecting us to do a man’s job. Why, damnit all, six months before the war broke they knew back home we were plenty weak out here and couldn’t hold off Japan. Before we started our big game of bluff with the Monkey Men, why in the hell weren’t we either reinforced, or packets sent out to take us home? We’d be a damn sight more good to our country sitting in on a well-equipped deal somewhere else than we’re going to be molding in the Jap prison camp.”

He stopped long enough to expectorate again toward a slow-moving cockroach, then went on: “What kind of game is this I’d like to know — slapping those official bulletins last month up on every other goddamn tree on Bataan — ‘Hundreds of planes and thousands of men will soon be here.’ ‘We will retreat no further.’ Yeah, that’s one for the book, boys.”

“Oh, take is easy, Buddy,” remarked an optimistic boatswain’s mate. “Our country isn’t going to forget our efforts here. Not by a damn sight. Why after the fun we had holding the Japs back so our country could get its breath — and helped save Australia from being swarmed all over by those yellow-bellies — we’ll be able to write our own ticket. Sure our government won’t let us down. Just wait until I walk in and dazzle my wife with gold braid on my sleeve. [ie, this enlisted Navy boatswain’s mate would become a Naval officer, who have gold braided insignia on their uniform sleeve.] And you, Sarg, aw you’ll be, maybe, a captain.”*

His companion gave him a sour grin and spat with vehemence at the roach just coming to life again.

“After that yarn about planes and men coming to our rescue, I am not interested in bedtime stories.”

Mustering a little enthusiasm, he hitched himself seaward and shading his eyes with his hand mimicked, “Sister Annie, Sister Annie, what do you see on the horizon? I’ll tell you what — sure I see a formation of goddamn planes, but sailor, they’re not flying our insignia.”

[The Sergeant is referring to the fairy tale “Bluebeard.” In it, Bluebeard is about to kill his wife. Hoping for her brothers to rescue her, she calls to her sister, “Anne, sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?” Sister Anne replies, “I see nothing but the sun, which makes a dust, and the grass, which looks green.” Eventually sister Anne sees two riders in the distance, who arrive in time to save the wife and kill Bluebeard. In other words, the sergeant is saying that the people he sees on the horizon are not Americans on their way to save these POWs.]

I smiled a bit wryly at this bit of satirical banter. This man wasn’t the only one who had visions of grandeur along these lines. It was just such hopes as was voiced which helped tide us over the rough spots later on. We had some consolation, however, as we gazed morosely up at the white flag of surrender. It was the fact that officers and men of these three arms of services — Army, Navy and Marine Corps — who fought in this campaign had held the enemy at bay for practically five months. This had contributed in conjunction with our small Naval force in the battle of Makassar Straits, and the battle in the Java Sea, and the allied defense on Java and Sumatra, in gaining valuable time to building up our defenses in Australia; to which our rescue convoy had been diverted to repulse the enemy’s plan to attempt and invade that continent. [Get historical context for these references here.]

A salute of courage

After the surrender, several Japanese tanks flanked by infantry and led by a Japanese officer with his heavy two-handed sword unsheathed appeared from on up the road. Standing near the side entrance or “escape hatch” of the Queen’s tunnel, which housed the Naval Headquarters, were two naval petty officers and myself.

On the road was a large pile of rifles, bayonets, small arms ammunitions, a few machine guns, World War I steel helmets, bandoliers, gas masks, etc. A good deal of similar war accouterments littered the immediate area. A small white surrender flag was planted on top of it. When the tanks arrived, the officer motioned us to move this surrender pile from the path of the tanks.

This completed, the Japanese officer grinning sardonically brandished his sword and started it coming toward us aimed at our heads. For just an instant a thought flashed through my mind, “We were going to be decapitated in the good old samurai manner.” But its course suddenly swerved upward descending with a heavy resounding thump on top of our heads in quick succession. For a moment we all were a little non-plussed.

Then the whole procession of tanks, trailed by a filthy-looking battalion of disheveled infantrymen in marching columns proceeded down the sloping, dusty road to their bivouac area of galvanized iron buildings. They were located in “Bottomside” near the small sourth harbor. These somewhat-damaged buildings were among the very few their bombs had not reduced to rubble. Later, I was informed that the cranial trouncing a la sword was a gesture of a rather crude Oriental compliment to us. It was supposed to be in recognition of courage for having put up a good fight. However recollecting the impact of that sword blade against our collective skulls convinced us otherwise.

Inside Queen tunnel

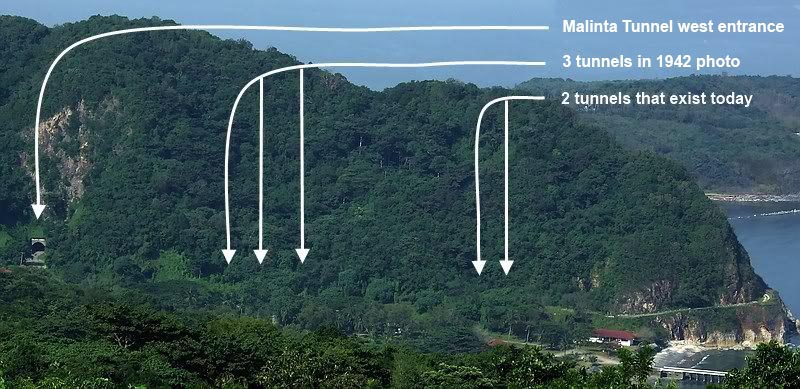

Queen’s tunnel, which extended also into Malinta Hill, was about six hundred feet long and contained several laterals of approximately seventy-five feet in length. At the end of the tunnel, the lateral running south therefrom was the “escape hatch” previously referred to, while the one extending northward several hundred feet connected with the huge Army Malinta tunnel, the largest of the labyrinth-like system of tunnels, laterals, and subterranean passageways that extended in all directions under Malinta Hill.

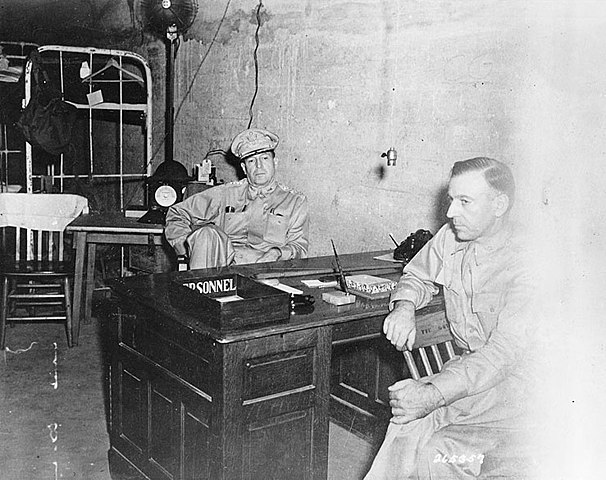

Queen’s tunnel was about twelve feel high, ten feet wide, and was arch-shaped very similar to a Quonset hut. It was completely cemented on the side and overhead with a concrete floor, painted white, and was electrically lighted. In the fore part near the curved entrance were several office desks which served as offices for the various marine and naval officers.

Further back in the tunnel, the laterals were utilized as radio room, administrative offices, including a finance office. In some laterals had been stowed cumbersome cases containing vital submarine spare parts. Several days before the invasion, we removed those spare parts under the cover of darkness and cast them over the high rocky cliffs into the sea.

The searches and confiscations begin

Later on that day in Queen’s tunnel, about one hundred fifty officers and enlisted men, mostly Naval and Marine personnel, were lined up in two columns about four feet apart facing each other at “attention.” While the Japanese officers over in the bivouac area in “Bottomside” were conveniently looking in the other direction, and thus giving tacit approval (a typcial Jap stunt), a small group of evil-looking Japanese soldiers walked slowly in front of us. They carried small short swords with a blade about fourteen to sixteen inches long similar to those worn by the Japanese police in Japan. They pointed these very menacingly toward our abdomens as a definite warning they would brook no interference nor delay in their looting for valuables such as watches, rings, money, etc.

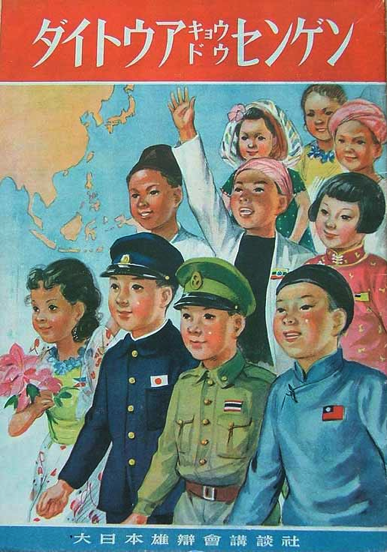

Needless to say, those who had not the forethought to conceal their possessions previously gave up “or else.” By this persuading method, I unprotestingly contributed my excellent Hamilton time piece — ”With Love”, from “Tottie” (my wife) engraved on its case — to the proponents of the “Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.”

It was not pleasant to be subjected to those moronic and unpredictable little monkey men. After looking us all over very carefully, digging into and searching bags, desks, as well as our persons, they left. One group of Americans in the rear of the tunnel were treated in a far more barbaric manner. The “Nippers,” as we referred to them so often, in frisking them practically denuded those prisoners by ripping their clothes off with bayonets fixed on the end of their rifles.

Time after time, new groups of Jap soldiers and marines entered the tunnel, and everyone had to immediately come to attention and submit to the galling procedure of being frisked and our belongings searched and strewn about. This continued throughout the day and into the night. In this pillaging and looting the Japs were running true to form.

Many Nip soldiers wore various Buddhistic charms, good luck annulets, and religious emblems to make them immune from injury during combat with the Americans. They carried them in little leather pouches or cases strapped to their belts and on other parts of their person.

Sneaking weapons past the guards

Just prior to the surrender, word was passed around orally in our sector that all weapons inside the tunnel were to be removed and placed in piles outside of the tunnels beyond our reach or control. No one was to have any arms concealed on their person. Accordingly all weapons, we thought, were cleared from the tunnels. However, during the day one of the Japanese tunnel sentries found a pistol concealed in a crevice which had been overlooked by our searching parties. He became very displeased and suspicious.

One of our Marine officers, Major Picek, who was formerly a Japanese language student in Japan and who was an accomplished Japanese linguist, spoke to the sentry very quietly and convincingly that we hadn’t hidden it intentionally. The suspicious Jap guard was pacified finally, and apparently accepted the explanation without his “find” reaching higher Japanese.

However, to be sure that our searchers in their haste had not overlooked more than this one pistol, we conducted a very thorough search that night in the tunnel. As a result, we had the reward of finding many more pistols, a couple of rifles, small arms ammunition, some bolos and bayonets, and a couple of hand grenades. All of these except the grenades were carefully boxed. The grenades were handled carefully and separately.

But now we were in a dilemma: How were we to get this contraband out of the tunnel and past the guard at the entrance without this coming to his attention? And if it did, God only knows, what possible repercussions would happen if he gained this intelligence. However, the ingenious American, even though a Jap prisoner, can rise to the occasion if the exigencies require it.

We accomplished its removal by taking advantage of the natural curiosity of the Jap by exhibiting something of interest to him and engaging him in conversation with a small knot of our men acting very pleasant around him; hemming him in as sort of a camouflage. This, together with the continual movement of pedestrians in and out of the tunnel, shielded our subsequent operations which consisted merely of doing the most obvious thing.

We carried out the few small boxes as though there were just harmless articles right under his nose without detection and nonchalantly dumped them on the pile of debris in the darkness not far from the entrance. At those early hours of the morning, very few Japs were in evidence near the tunnel. It is needless to relate, we were extremely relived at the success of this small but important chore.

We felt if they had found out or were even suspicious of the fact that there were any more arms that had not been surrendered it would have positively confirmed in the minds of those intensely suspicious natures that we were merely holding them to be used against them later on, and it would also presage that there might be a greater cache elsewhere in those underground passages. I suppose psychologically this was a reasonable thinking process of their minds because they think and do anything that employs cunning or trickery to gain an advantage at a precise time when the element of surprise is the greatest factor.

Day 2 of captivity dawns

During the day, men were assembled in small groups on the western slope of Malinta Hill. Some of them began to kindle small fires on which they prepared individual cooking. For two or three hours in the morning, the men sought refuge there from the sun. This side of the hill was shady during that time but as the searing sun rose higher there was little protection, even in this area, from the almost unbearable heat.

The tunnels gave protection from the sun for some, although the air here was hot and humid and almost foul at times due to the large number of men. Hundreds “dug in” all over the five-mile square island in individual fox holes. Their lives up to the time of surrender had been plenty rugged indeed.

The Japanese soldiers remained in their own areas for the most part. However, one or more individual pots of rice could be seen stewing away near us. The common Jap soldiers under these circumstances did his own cooking as well as cooking and acting as flunkey for his “non-coms.” As soon as they had prisoners or captives, they were relieved for the most part of these menial tasks.

Pineapple and prize fish

The night of the surrender [May 6, 1942], an unusually tall Japanese corporal, at least six feet, carrying a saber poised to weild, came up to us. In great excitement and anticipation he kept plaguing us by screaming for canned pineapple! — pineapple! These Japs seemed to have an insatiable appetite for American canned pineapple. In this particular incident, he conscripted me to help him and literally pushed all over the tunnels and laterals to find stocks of it among hundreds of cases of other tinned provisions stowed away.

After locating it, he of course utilized our officers and men as coolies to move all cases of pineaple out of the tunnel down to “Bottomside” in the Japanese bivouac area. Our first lesson in humiliation a la Nipponese began immediately upon becoming their “prize fish.” A short distance away I saw a cluster of Jap privates reveling in this glory.

A number of our officers and men were conscripted to perform all types of menial and personal services for the Jap non-coms and privates such as carrying their bags, carrying water for them, and washing their filthy clothes. Of course they now owned us body and soul, and our treatment was that which was accorded a pagan slave. But this was only a beginning. Our captors has disregard and contempt for the Geneva Convention and the International Rules of War.

Every now and then, some Japanese soldier would screech out to us and motion a task to be performed. Language difficulties did not help the situation by any means. They could speak or understand very few, if any, American words, and except for possibly a few among us, we were at a similar disadvantage. But the disadvantage in this respect was all ours because if we didn’t comprehend “hassili” (meaning “in a hurry”) they immediately instituted some punitive action against us.

The soldiers repeatedly returned to the tunnels to re-search us. Watches, especially wrist watches, were apparently first on their priority lists. One Jap non-com had a string of wrist watches on his arm that reached up to his elbow.

We theorized and speculated upon what the Japs would do with us. We were totally without a career, without a future, and completely stripped of our perogatives as free men. Down, down, down, we cascaded until we were reduced to that particular slavery, the type of which only a despotic Oriental power knows how to inflict. We could in no manner excercise our own volition in a practical manner.

Read next

Please share

If you think Salm’s memoir is worth passing along to friends or family, we’d love for you to share the link to this post on social media or email. Thank you!

Notes

- I have tried to figure out who the unnamed grumpy Sergeant was. Unfortunately there are too many possibilities to positively identify him.

Images

- Image 1: Douglas MacArthur. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo, March 1941, public domain, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MacArthur_and_Sutherland_s265357.jpg, accessed 3 July 2019.

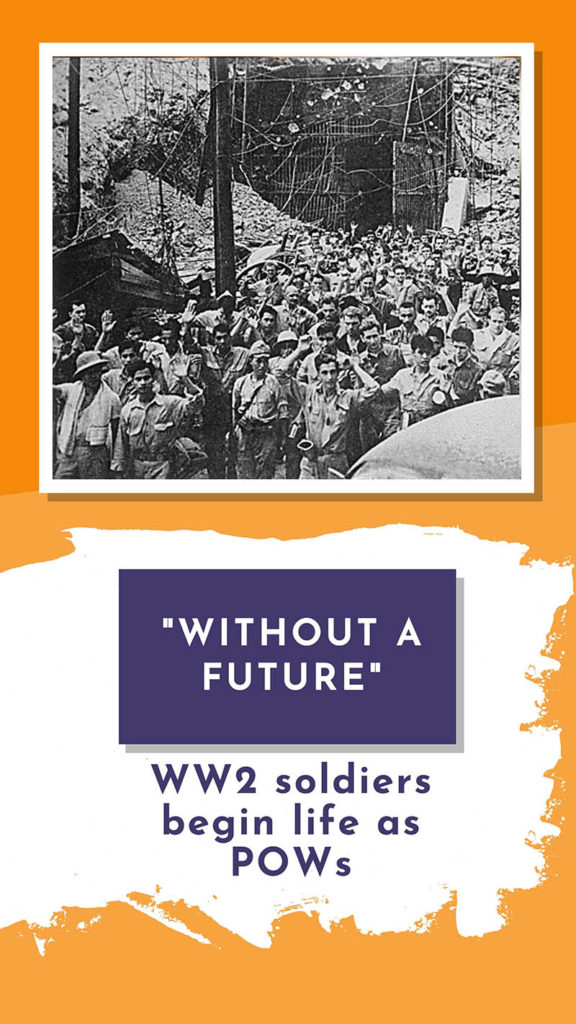

- Image 2: American Sailors at Queen Tunnel. From the collection of Captain Paul Ashton, M.C., posted by chadhill on Corregidor: Then and Now Propoards, online at http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/852/malinta-navy-tunnels, accessed 26 June 2019.

- Image 3: Modern-day diagram of Malinta Hill. Posted by Fots2 on Corregidor: Then and Now Proboards, online at http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/852/malinta-navy-tunnels, accessed 26 June 2019.

- Image 4: 1942 image of 3 Navy tunnels on Malinta Hill. Posted by Fots2 on Corregidor: Then and Now Proboards, online at http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/852/malinta-navy-tunnels, accessed 26 June 2019.

- Image 5: Emily Hunt Salm, ca 1918. In personal collection of Anastasia Harman.

- Image 6: Japanese propaganda. Cover to the “Declaration of Greater East Asian Co-operation” pamphlet published by Dai Nihon Yubenkai (Great Japan Debate Society), Kodansha, 1942, found online at James Orr, “A 1942 Declaration for Greater East Asian Co-operation,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, https://apjjf.org/-James-Orr/2692/article.html, accessed 27 June 2019.

- Image 7: Portrait of Frank Peter Pyzick. Yearbook of the US Naval Academy, 1926, found online in “US School Yearbooks,” Ancestry.com, search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=yearbooksindex&h=1073<br/>1243&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt<br/>, accessed 1 July 2019.

![“Without a future”: Corregidor’s defenders begin life as POWs [Memoir #3]](https://www.anastasiaharman.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MalintaNavytunnels1-367x571.jpg)

Anastasia,

Stumbled upon your web site while researching the facts surrounding my wife’s uncle’s circumstances during WWII, which ended in his death in a Japanese POW camp/hospital. He was a shipmate of Alma Salm on the USS Canopus. Robert Lewis, GM3, died July 5, 1945. Cause of death was listed as tuberculosis. I have found that he was in Osaka Main Camp Chikko, but was placed in Kobe POW Hospital on May 22, 1945. Kobe POW Hospital was bombed and destroyed by American B-29s on June 5, 1945, and Robert suffered serious burns in this incident. All of the above led to his passing a month later, just a little more than month before the end of the war. His ashes are buried in his family’s plot on St. Simon’s Island, GA. I’ve always wondered if those are really his ashes buried there, but the book I’m reading has somewhat assured me due to the Japanese(at least in Osaka) apparently took great care of the POWs’ cremains by boxing them individually, labeling them, and storing them in a Buddhist temple in Osaka that was later recovered by the Americans.

I am currently reading “Ghosts of Canopus – The War Diary of a Lucky Lady”. I would imagine you have read this book. From this book and from having located some documents on-line mostly from the U.S. Archives (but I found them on a Filipino web-site), I have learned more than I had known regarding Robert’s situation from May, 1945, to his death a month and a half later. What I haven’t found is his specific situation in the Philippines. Most Canopus sailors ended up surrendering on Corregidor in May, 1942. I assume he was part of that group, but don’t know for sure. I believe a handful of Canopus sailors were sent ashore and blended in with Marines’ ground forces and had to endure the original Bataan Death March. Nor have I learned what POW camp in the Philippines he was sent to or the hell ship he ended up on to be transported to Japan. His initial assignment was to the USS Permit, one of the submarines assigned to the Canopus. At some point prior to December, 1941, Robert was transferred to the Canopus. Circumstances behind that transfer are likely to never be known. Did he suffer from claustrophobia and the submarine was not for him? The irony is, if he had remained on the submarine, he likely would have survived the war.

I’ll read all of the stories you and your great-grandfather have provided to further enlighten me to what were the horrendous conditions were for Gunner’s Mate Lewis and all the other brave vets. To plagiarize Tom Brokaw, truly the Greatest Generation.

Thanks,

Brad Wolfe