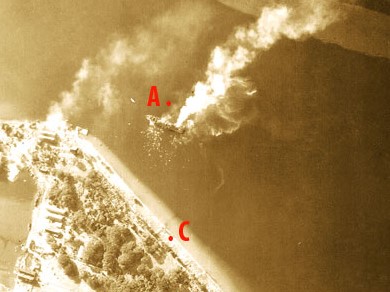

Everything was in flames.

It was dark by 7 pm the day after Christmas, 1941. The Philippine temperatures, although probably dropping to the low 80s, would have been warm enough.

No need for a warm winter fire.

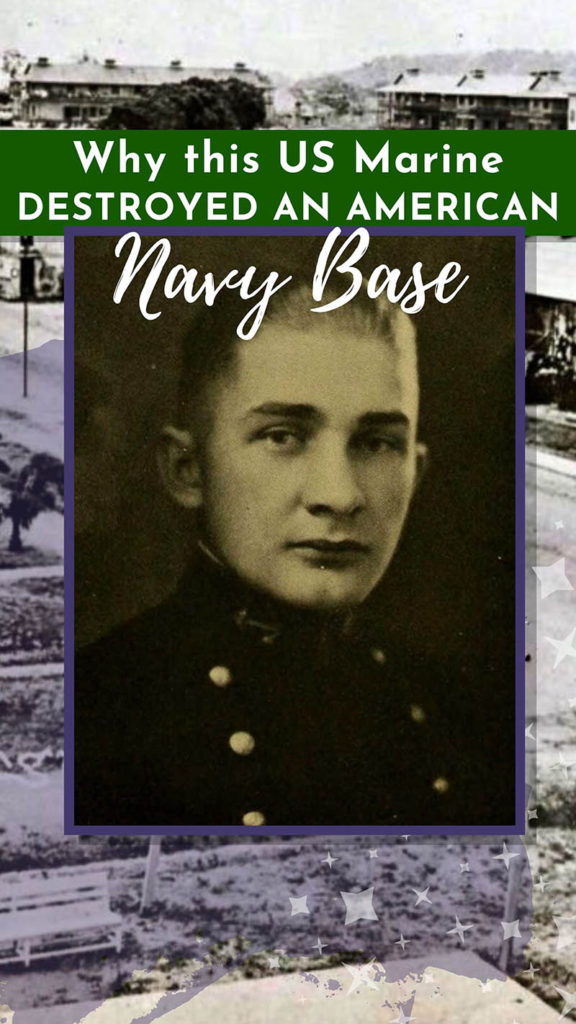

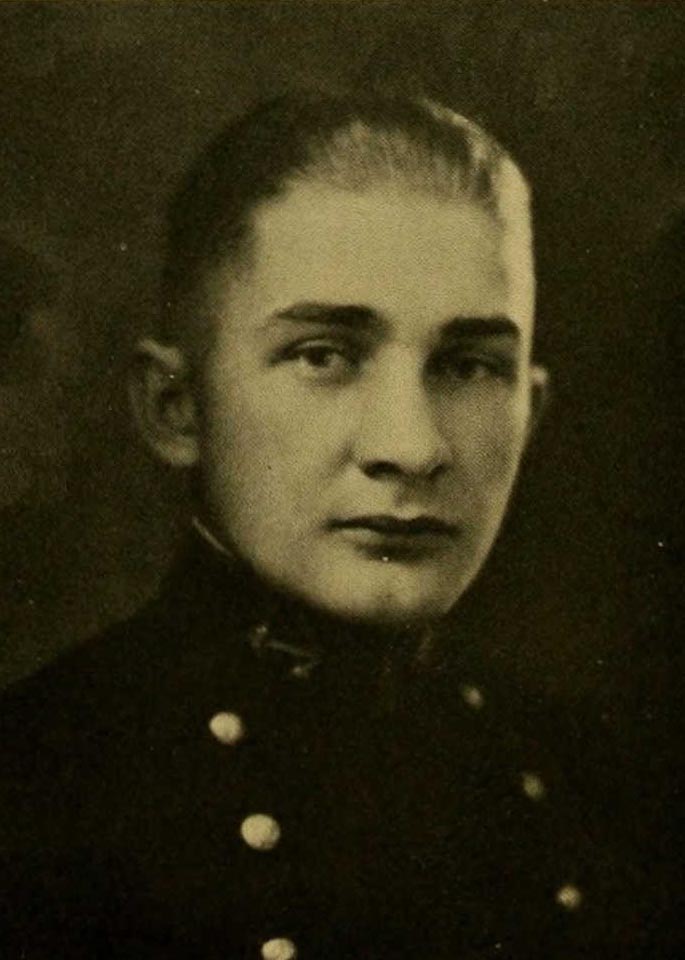

But the fire light wouldn’t have shown holiday revelers. Instead it probably illuminated the retreating form of Major Frank Pyzick, US Marine Corps, who had just destroyed an American navy yard.

Major Pyzick was a 15-year veteran of the Marines and a graduate of the US Naval Academy, where his classmates described him as having a “retiring disposition” and “the temperament of a divine.”

But on this day — December 26, 1941 — he had detonated explosives all over the Olongapo Navy Yard on Luzon island in The Philippines, sunk a US ship, and destroyed as many submarine parts as could be found.

Everything that hadn’t been blown up was doused with fuel and set on fire. And then he headed into the Luzon jungle.

A US Naval Academy grad

Frank Peter Pyzick was born September 27, 1902, in a small southern Minnesota town called Wells. He was the 4th child born to Michael and Anna Pyzick, who were Polish and German immigrants. Michael worked as a carpenter.

Frank grew up in Wells and worked there as a grocery salesman in his teens.

In the early 1920s, he headed east to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Midshipman “Zick” was quiet, “small of stature,” and always in a hurry. He was a dedicated student who was interested in radios and had an “absolute disregard” for girls.

From Tokyo to the 4th Marines

After graduating from Annapolis, Pyzick was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant in the US Marines in June 1926. He spent the next couple years at various Navy and Marine stations in the US.

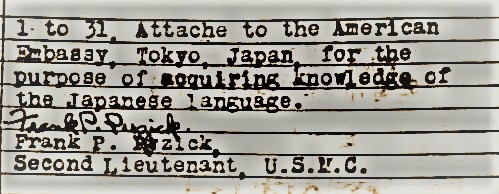

In October 1928, he was transferred to Japan. For three and a half years, he was part of the Naval Attaché’s office at the American Embassy in Tokyo. He was there “for the purpose of acquiring knowledge of the Japanese language.”

He left Tokyo in early 1932 and spent the rest of the 1930s assigned to various bases and ships around the US.

Captain Pyzick sailed to China in summer 1939 to join the 4th Marines regiment in Shanghai. He would spend nearly 3 years there, earning the rank of Major and joining the regiment’s headquarters.

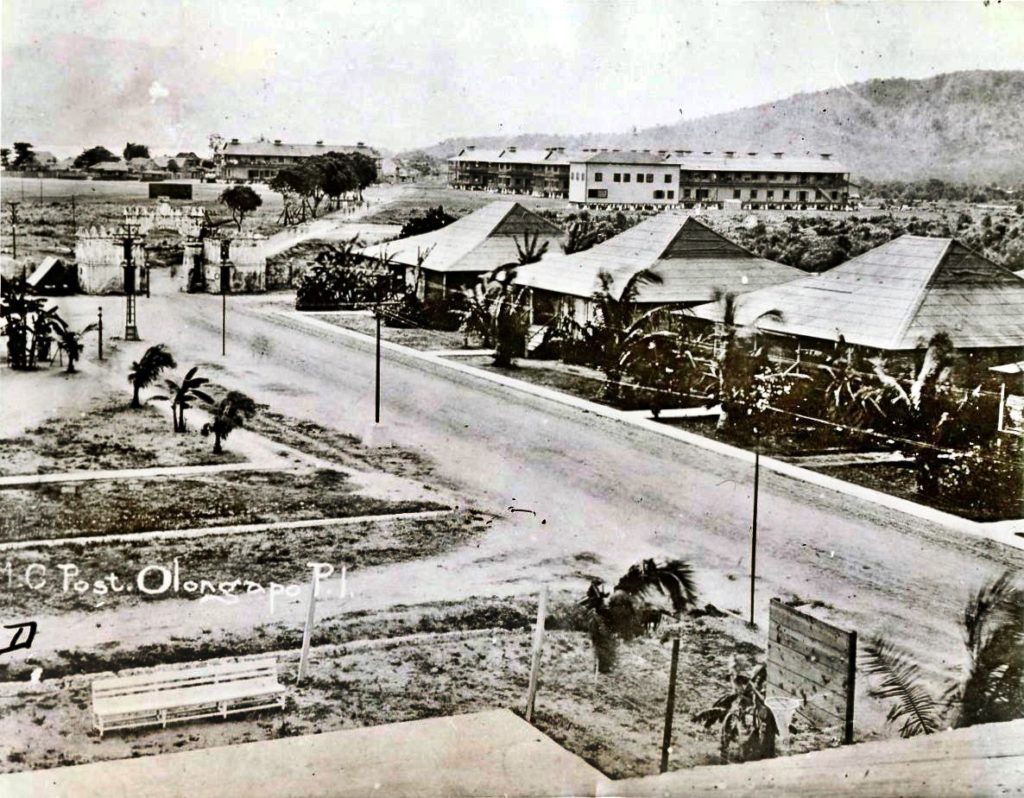

Then, in November 1941, the 4th Marines Regiment left Shanghai. They boarded a ship and en route discovered their destination — Olongapo Navy Yard in The Philippines.

Their task: Assist in preparations for an anticipated Japanese invasion.

World War 2 comes to The Philippines

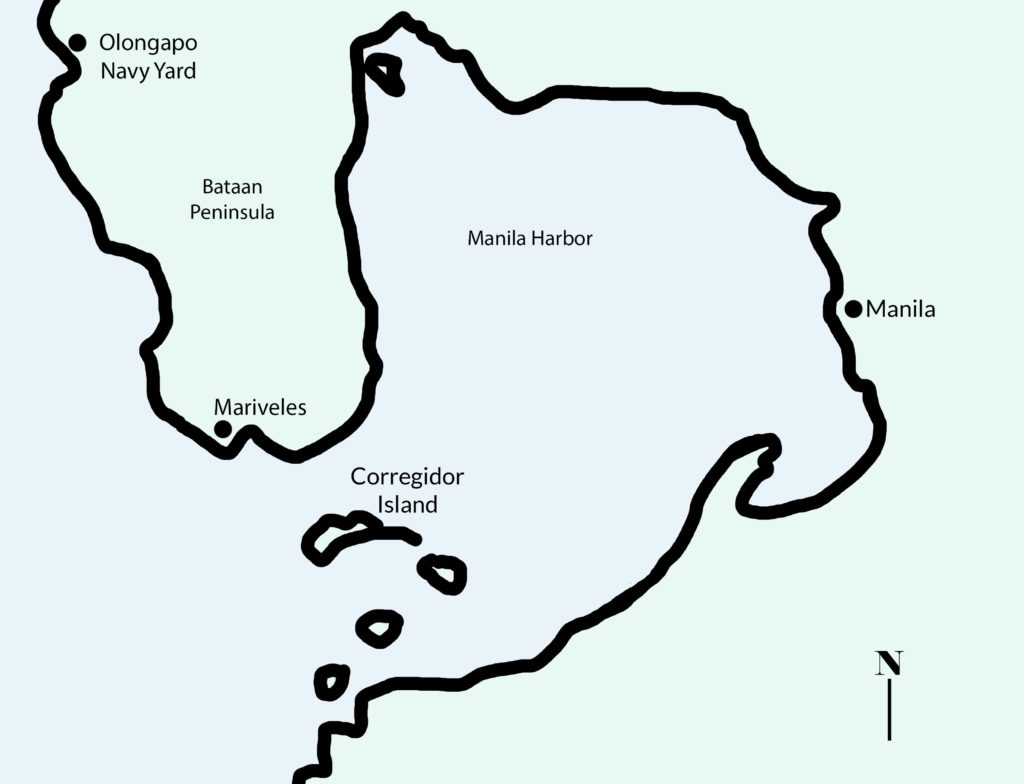

Major Pyzick arrived at Olongapo on either November 30 or December 1, 1941. The 4th Marines bunked in warehouses converted into barracks. And they started training, day and night, in the nearby Bataan wilds.

War, as it turned out, was closer than perhaps expected.

December 8, 1941, 3:50 am (Philippines time). The Marine Barracks at Olongapo Navy Yard received word that Pearl Harbor had been attacked.

The United States was at war with Japan.

In those early morning hours, Pyzick, the officer of the day, climbed into a motorcycle’s side car. And, like a modern Paul Revere warning of the coming British, Pyzick shouted “War is declared! War is declared!” as the motorcycle rode through the Navy Yard.

The Japanese immediately began bombing Manila, about 50 miles away. But 4 days would pass the Marines at Olongapo saw war.

Destroying the Olongapo Navy Yard

At 10:20 am on December 12, 1941, Japanese fighter planes began strafing runs over Olongapo. The Marines opened fire on the aircraft, but their efforts did little.

27 Japanese bombers arrived the next morning, attacking the yard and city of Olongapo. Tokyo Radio reported that the bombers had wiped out the 4th Marines. But they hadn’t.

Over the next week, the 4th Marines set up defensive and blocking positions along beaches and roads near Olongapo and the Bataan Peninsula. Japanese landed north of Olongapo on December 22, and the Marines prepared to defend the Navy Yard.

But keeping the yard wasn’t possible. The Japanese had overrun so much of Luzon island that General Douglas MacArthur ordered all American military into the Bataan Peninsula for a last stand.

The 4th Marines moved south to Mariveles on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula.

And Major Frank P. Pyzick, with a detachment of Marines under his command, destroyed Olongapo Navy Yard on December 26, 1941 — to keep weapons, supplies, and more from falling into enemy hands.

Escape to Corregidor island

After destroying the Navy Yard, Pyzick retreated to Mariveles on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula. The next night, December 27, he and the rest of the 4th Marines regiment headquarters relocated to Corregidor island under cover of darkness.

And there Frank Pyzick stayed for some 4 months, under almost constant bombardment as the Japanese laid siege to the island military base guarding Manila Bay.

Supplies — especially food and water — were running low for the island’s more than 10,000 military personnel. The men were hungry, dehydrated, and malnourished. Some of the 4th Marines lost 40 pounds during their time on Corregidor.

The 4th Marines took charge of that island’s beach defenses. And there, early on a May morning, they would be the first line of defense against the invading Japanese troops.

But Corregidor fell to the Japanese. And in the early afternoon of May 6, 1942, Major Frank P. Pyzick became a prisoner of war.

Saved by speaking Japanese

Pyzick’s first act as a POW may have saved the lives of himself and several POWs.

Before surrendering, the American Navy and Marine personnel discarded their weapons. Guns, grenades, and more were piled outside the Malinta Tunnels. No one could have personal weapons. And the barracks, offices, and other parts of the tunnel system needed to be completely cleared of weapons.

So Pyzick and the other servicemen complied.

Or so they thought.

After the surrender, a Japanese sentry found a pistol hidden in a tunnel crevice. It was an oversight.

But the Japanese sentry was suspicious and angry. And suspicious, angry guards could mean punishment or death for the prisoners.

Luckily for the POWs, Major Pyzick knew Japanese. Alma Salm recorded that Pyzick:

spoke to the sentry very quietly and convincingly that we hadn’t hidden it intentionally. The suspicious Jap guard was pacified finally, and apparently accepted the explanation without his “find” reaching higher Japanese.

Alma Salm, Luzon Holiday, pages 10-11

The anxious POWs then re-searched the tunnels to make sure there were no hidden weapons.

An American POW in The Philippines

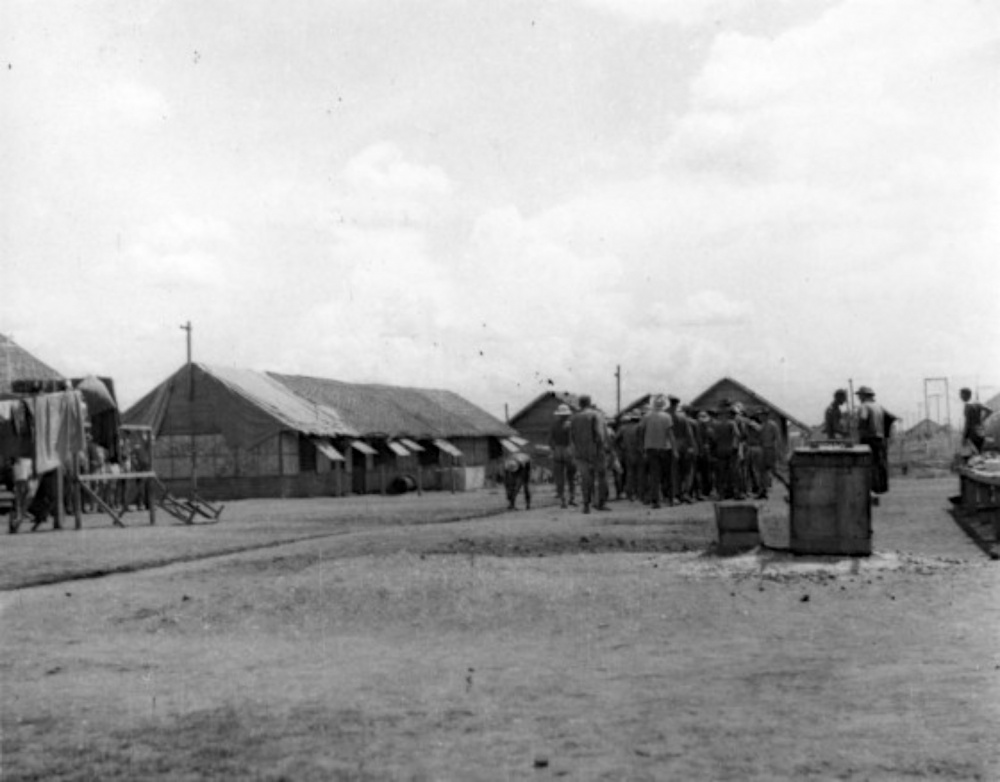

The Japanese eventually transported Pyzick and the other Corregidor prisoners to Manila and marched them through the city. The prisoners were then crammed into hot, stuffy railroad boxcars for a 70-mile journey to Cabanatuan city. Then they had a 16-mile march to Cabanatuan prison camp #3.

Life in the Cabanatuan prion camps was torturous. Like most men in the camps, Frank Pyzick would have suffered starvation, malnourishment, diseases, beatings, and heavy, hard, back-breaking work.

He served as Statistical & Personnel Officer in the Cabanatuan camp #1 Headquarters Staff. In total he spent 31 months as a POW in The Philippines. But his time as a prisoner wasn’t over yet.

Surviving 3 hell ships and 2 shipwrecks

The American military returned to The Philippines in late 1944. In response, the Japanese relocated some Allied POWs from The Philippines to the Japan mainland.

On December 13, 1944, Frank Pyzick entered the forward hold of the Japanese hell ship Oryoku Maru in Manila. More than 1,600 POWs were in the ship’s 3 holds as it sailed around the Bataan Peninsula.

But the ship wasn’t marked.

The US Navy planes had no way of knowing what cargo the enemy ship contained when they attacked the Oryoku Maru on December 15.

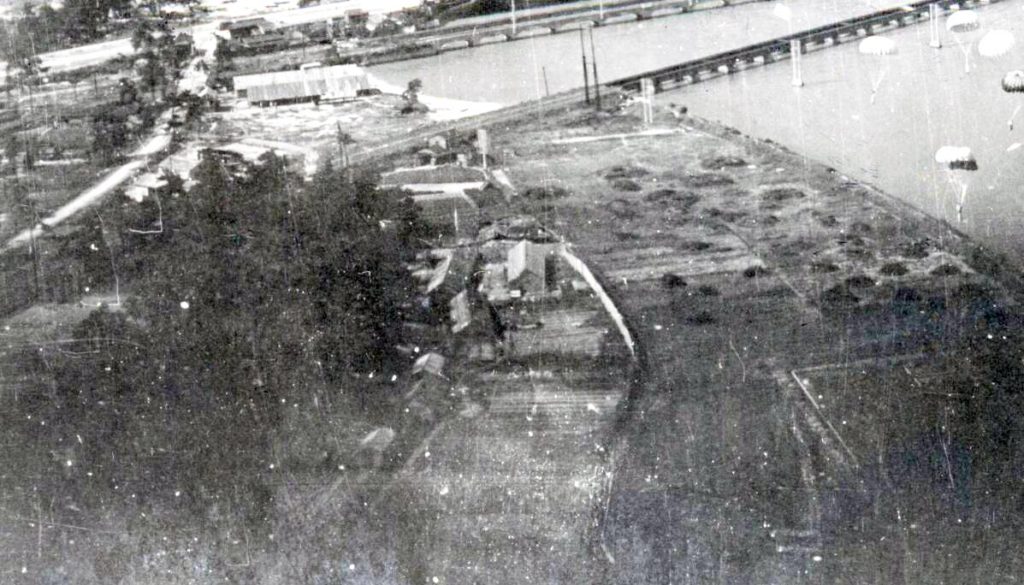

Pyzick escaped the sinking ship, swam to shore, and found himself in familiar territory — Olongapo Navy Base. He and the other POW survivors spent several days on the base’s tennis court before being transported overland to San Fernando, about 100 miles north.

Here Frank Pyzick was loaded onto either the Enoura Maru or the Brazil Maru. Both of these “hell ships” sailed from The Philippines just two days after Christmas in 1944. They reached present-day Kaohsiung, Taiwan, on New Years Day 1945. The POWs spent more than 2 weeks in that harbor, still aboard the torturous hell ships.

And during that time, Pyzick again survived an American air attack while he was on board the Enoura Maru.

Pyzick and the other 900 survivors transferred to the Brazil Maru, which arrived in Moji, Japan, on January 29, 1945. He had spent a month and a half on Japanese “hell ships.” He was one of 550 POWs — of the original 1,600 — who survived the trip.

Pine Tree Camp in Fukuoka, Japan

13 years after leaving the Tokyo US Embassy, Major Pyzick again found himself in Japan. Only this time he wasn’t part of the diplomatic mission — he was a Japanese prisoner.

The POW camp in Fukuoka City was Pyzick’s Japan destination. This camp, which the prisoners called the “Pine Tree” camp, was new, the buildings still under construction. The POWs endured the winter weather in small, unheated barracks where they slept on sand. As an officer, Pyzick’s work in this camp would have included gardening and hauling human waste.

Within months, however, American bombings of Japan soon forced yet another prisoner move.

On April 25, 1945, Maj. Pyzick and about 140 other prisoners left the Pine Tree Camp and were ferried to Korea. A train ride across the Korean peninsula brought them to the Jinsen POW camp near present-day Seoul, Korea.

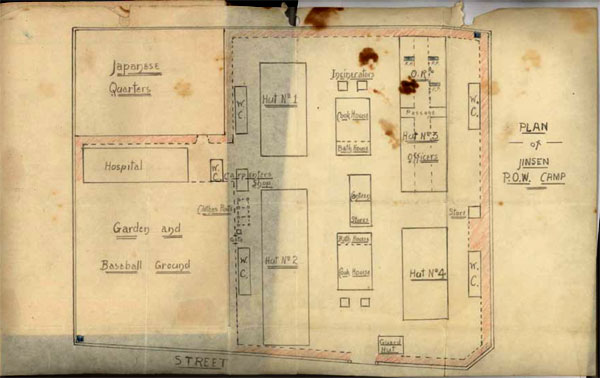

The Jinsen, Korea, POW camp

Life at the Jinsen camp was probably the best Major Pyzick experienced during his nearly 3 and a half years as a POW. Morale seems to have been better here than at other camps, and the Japanese official governing this camp was even described as “kind.” Prisoners worked pulling rickshaws and paving roads.

As the war’s end neared, the Japanese guards looked more and more despondent, and camp security became less strict. One day the officer prisoners at Jinsen camp, perhaps including Major Pyzick, were brought to the Japanese Camp Commandant, who told them the war was over and offered them Saki to celebrate “no hard feelings.”

By September 9, 1945, Frank Pyzick and all the other Jinsen POWs had boarded evacuation ships and headed, once again, for The Philippines.

Frank Pyzick then flew from the Sangley Point Navy Base (near Manila) to Honolulu, Hawaii, arriving on September 27, 1945.

After 40 months of captivity, and more than 6 years in Asian countries, Frank Pyzick was once again a free man on American soil.

It was also his 42 birthday.

Post-war peace in Pebble Beach

Pyzick’s life after WW2 has been less forthcoming.

By July 1946 he had achieved the rank of colonel and was working in Headquarters at the San Diego, California, base. He retired from the Marine corps in December of the same year — just 14 months after being liberated.

In total, he served as a US Marine for 20 years.

Sometime after World War Two, he married Mamie Elanora Bolstad, who was 12 years older than Frank and was from his hometown of Wells, Minnesota.

Frank and Mamie did not have children, as far as we can discover.

At some point, the couple moved to Pebble Beach near Monterrey, California. Mamie died there in 1975. Frank followed two years later on December 31, 1977. He was 75.

Final Thoughts

What strikes me about Major Pyzick is that I’ve been able to discover so many details about his experiences as a Marine and as a POW, but that details about his life after the war are so incomplete.

Records created after 1950 aren’t super easy to access. (Privacy laws — gotta love ’em and hate ’em…) But I’ve been able to discover quite a bit about other POWs’ lives post-WW2. Why so much radio silence on Pyzick?

I can’t even find that he was buried in a veteran’s cemetery.

Alma Salm and Pyzick’s Naval Academy buddies described Frank as quiet and mild mannered. Perhaps, after the war, he just lived a quiet, unassuming life.

I also am struck by how much a human can endure. Maj. Pyzick had endured difficult POW camps for 2 and a half years before he boarded that hell ship. He then survived 2 ship bombings and 2 sinkings. Only a third of the original POWs were alive when the last ship reached Japan. Frank was one of them; and he was in his late 40s. Remarkable.

What strikes you about Major Pyzick and his POW experiences? I’d love to hear about it in the comments below.

Now it’s your turn

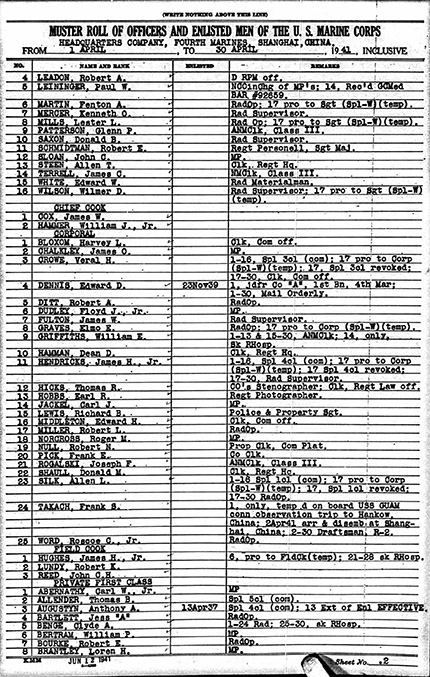

The hands-down most helpful resources in tracing Maj. Pyzick’s life were Marine Corp Muster Rolls.

Muster rolls are basically lists of individuals currently attached to a specific military unit. The rolls often include an individual’s name, rank, station, enlistment date, and remarks.

I used a Marine Corp Muster Rolls database that covers 1798-1958.

Frank Pyzick’s name appears on a muster roll roughly every two months from 1926 to 1946. So I was able to track Frank Pyzick’s Marine service, stations, and movements during the entire 20 years he was a Marine. (Except for during his POW period.)

Muster Rolls are an awesome resource for finding people who served in the military. And there are muster rolls for other military branches besides Marines.

But if you do have Marines in your family, here’s where you can find the Marine Corps Muster Rolls that I used:

- In digital format on Ancestry.com.

- On microfilm at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC. Regional NARA branches offer free access to the digital records on Ancestry.

- At Family Search, but their collection covers 1798-1937. They’re the same docs as on Ancestry, however the rolls from 1893-1937 aren’t all indexed (which makes finding rolls docs about specific people difficult).

Read Next

Please help us share Major Pyzick’s story

You can help us honor Frank Pyzick and his courage, sacrifice, and service by sharing his story on social media or with friends. Thank you!

Sources

- Ancestry.com. Honolulu, Hawaii, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Passenger and Crew Manifests of Airplanes Arriving at Honolulu, Hawaii, compiled 02/1937 – 11/1954; National Archives Microfilm Publication: A3614; Roll: 05; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 – 2004; Record Group Number: RG 85.

- Ancestry.com, “U.S. School Yearbooks,” online publication, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, Original data from various school yearbooks from across the United States, online at search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=yearbooksindex&h=1073<br/>1243&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt<br/>, accessed 23 July 2019.

- Ancestry.com, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958, database online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/marine_muster/, original data from U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893-1958, Microfilm Publication T977, 460 rolls. ARC ID: 922159. Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127; National Archives in Washington, D.C. , accessed 7 July 2019.

- Ancestry.com. U.S., Navy and Marine Corps Registries, 1814-1992 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017. Original data: Navy Department Library – Naval History and Heritage Command; Washington, D.C.; Navy Register: Retired Officers of the U.S. Navy; Year: 1966 (v.1), U.S., Navy and Marine Corps Registries, 1814-1992. Navy Department Library – Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

- “Appendix C: Marine Task Organization and Command List,” History of the U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, found online at http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/I/USMC-I-A-C.html#fn1, accessed 8 July 2019.

- Cheryl Magnant, “Long-forgotten WWII POW Camps in Korea,” on EthnoScopes: Tracks of an Anthropologist, online at https://ethnoscopes.blogspot.com/2013/10/long-forgotten-wwii-pow-camps-in-korea.html, accessed 8 July 2019.

- Colonel Wibb E. Cooper, Medical Corps, Medical Department Activities in The Philippines from 1941-6 May 1942 and Including Medical Activities Japanese Prisoner of War Camps,” written April 1946, found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/Page04.htm#Goodpasture, accessed 10 July 2019.

- Harold K. Johnson, affidavit on experience as a POW, found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/USAffJ-P.htm, accessed 10 July 2019.

- J. Michael Miller, “From Shanghai to Corregidor: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines,” online at Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003140-00/sec1.htm, accessed 5 July 2019.

- James W. Erickson, complier, “Oryoku Maru Roster,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/Erickson_OM.htm, accessed 9 July 2019.

- James Sinclair, “Singapore to Jinsen: Tracey George Clifford Sinclair,” Far Eastern Heroes, found online at http://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/Singapore_to_Jinsen/, accessed 10 July 2019.

- “Jinsen Camp – Korea,” Far Eastern Heroes, found online at http://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/Richard_Swarbricks_War/html/jinsen_camp_-_korea.htm, accessed 10 July 2019.

- “Korea (Chosen),” in Prisoner of War Camp Conditions on the Asiatic Mainland, dated 1 July 1944, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/POW_Camp_Conditions_Asiatic_Mainland_1944-07-01-s.pdf, accessed 10 July 2019.

- “Ōryoku Maru,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ōryoku_Maru, accessed 9 July 2019.

- “Report on American Prisoners of War Interned by the Japanese in the Philippines,” Center for Research: Allied POWs under the Japanese, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/Cabanatuan/cabanatuan_1.html, accessed 9 July 2019.

Images

- Image 1: Aerial view of Olongapo Navy Yard. Navy Historical Center Photo 80-G-1783219, found online at J. Michael Miller, “From Shanghai to Corregidor: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines,” Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003140-00/sec6.htm, accessed 23 July 2019.

- Image 2: Photo of Frank Pyzick. Ancestry.com, “U.S. School Yearbooks,” online publication, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, Original data from various school yearbooks from across the United States, online at search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=yearbooksindex&h=1073<br/>1243&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt<br/>, accessed 23 July 2019.

- Image 3: Tokyo Muster Roll. Ancestry.com, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958, database online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/marine_muster/, original data from U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893-1958, Microfilm Publication T977, 460 rolls. ARC ID: 922159. Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127; National Archives in Washington, D.C. , accessed 7 July 2019.

- Image 4: 4th Marines leave Shanghai. From the John E. Drake Papers, Personal Papers Collection, Marine Corps Historical Center, Washington, DC, found online at J. Michael Miller, “From Shanghai to Corregidor: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines,” Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003140-00/sec1.htm, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Image 5: Bataan and Manila Harbor map. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 6: Olongapo Navy Yard. International News Photo from Olongapo Post, King Features Syndicate, New York, NY, taken 12 December 1941, found online at http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/1541/subic-bay-sbfz-naval-base?page=8, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Image 7: POWs at Cabanatuan camp. From the MacArthur Memorial Library, Norfolk, Virginia, public domain, found online at Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, https://www.dvidshub.net/image/3587783/cabanatuan-prisoner-war-camp, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Image 8: Ōryoku Maru sinking. US Navy photo, public domain, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oryoku_Maru_aerial_attack.jpg, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 9: Pine Tree Camp. “Prisoner of War Camp #1: Fukuoka, Japan,” found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/Page01.htm#Locations, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 10: Jinsen Camp Layout. Found online at “POWs in Japan and Korea,” Australia History Museum, Macquarie University, https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/image/0010/99964/ricketts-plan.jpg and https://www.mq.edu.au/about/campus-services-and-facilities/museums-and-collections/australian-history-museum/online-exhibitions/selarang-to-sonkurai-australian-history-museum/selarang-to-sonkurai-australian-history-museum, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Image 11: Pebble Beach. “Coastline along the 17 Mile Drive in Pebble Beach of Monterey,” Adobe Stock Images, used by permission, licensed 24 July 2019.

- Image 12: Shanghai Muster Roll. Ancestry.com, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958, database online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/marine_muster/, accessed 5 August 2019.