Japanese airstrikes all but destroyed the US Army Air Corps in and around Manila.

But the aircraft loss was likely not on Dr. Lloyd Goad’s mind the afternoon of December 8, 1941. Nor the fact that it was his 28th birthday.

No, Major Goad, US Army Medical Corps, would have been focused on shrapnel wounds and burns from the airfield explosions. Bullet wounds from aircraft strafing.

Wounded soldiers poured into Sternburg General Hospital, the US military hospital in Manila, from at least 4 greater-Manila-area airfields.

And the causalities only kept coming, as Japanese forces next turned their attention to the nearby naval and army bases and to the US ships in Manila Bay.

Major Goad’s fight was to save his patients, the servicemen sacrificing themselves in these first days of WW2.

As December progressed, Japanese invasion forces moved ever closer to Manila. Dr. Goad’s own life would soon be in danger.

Was escape and self-preservation even an option for an Army doctor in a WW2 war zone?

1. They prepped for medicine, not for war

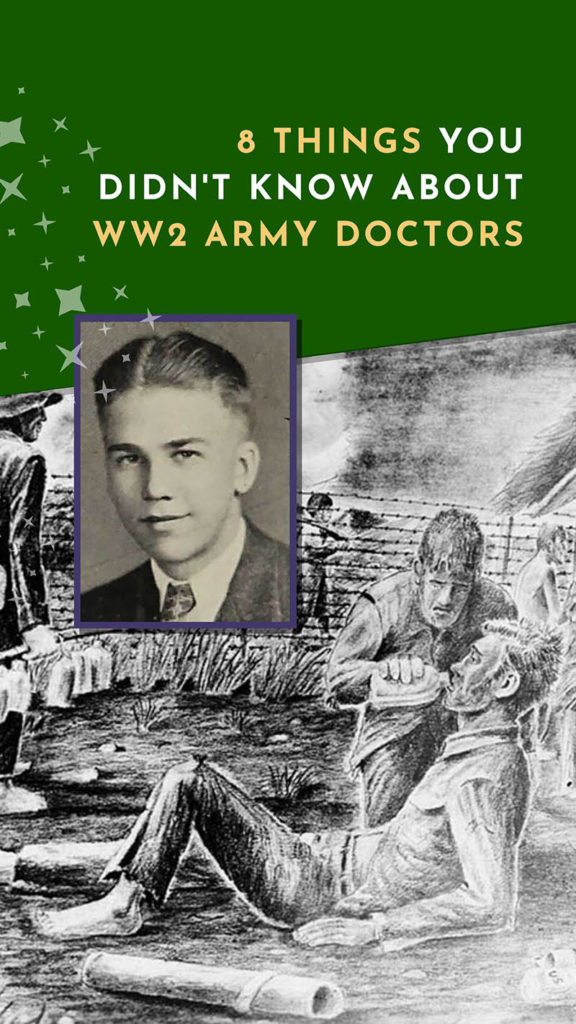

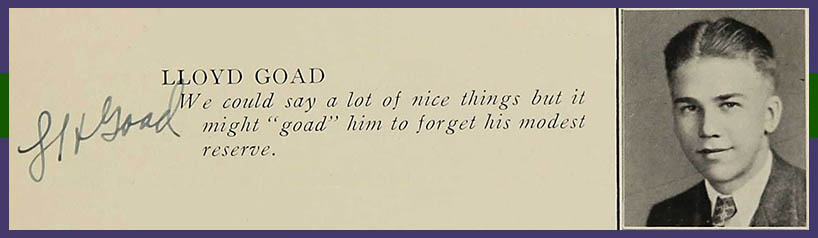

Lloyd Henry Goad grew up, as we’d probably say today, “privileged.”

Born December 18, 1913, Lloyd was the oldest of Rosa and James Goad’s 2 sons. James was a physician, and in 1930 the family not only had a live-in housekeeper, but their Gary, Indiana, home was worth $20,000. That was 2-3 times the value of neighboring homes..

Lloyd graduated from Mann High School in the early 1930s, then attended the Indiana University School of Medicine. By 1940 he was a resident at Oklahoma City General Hospital in Oklahoma.

But Army service came calling, and he’d soon traded his Oklahoma City residency for Army hospitals in The Philippines.

And his years of medical school and training could not have prepared him for the experiences he’d endure in the next several years.

2. They retreated with everyone else

As Major Goad worked to save lives at Sternburg Hospital during December 1941, the city around him was under attack.

Air strikes. Bombings. Strafings.

They all became common place in Manila as Christmas 1941 neared. The Japanese infantry was swiftly approaching that capital city. Dr. Goad was practicing medicine in the midst of war.

Then the US ordered all military personnel — medical staff included — to retreat from Manila.

Major Goad likely found himself among a medical caravan of doctors, nurses, patients and other staff making their way from Manila to the Bataan Peninsula on December 20, 1941.

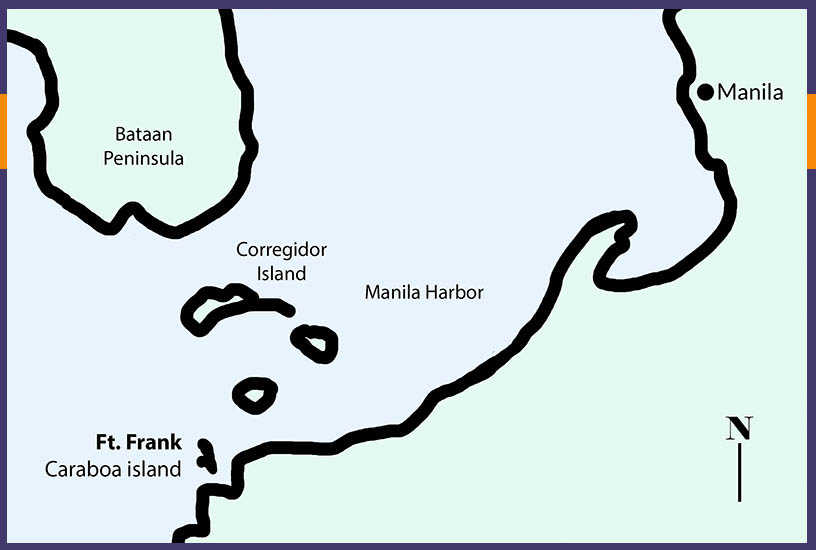

He was then assigned to Fort Frank — an island that guarding the entrance to Manila Bay. Dr. Goad would again be practicing medicine under constant attack.

3. Their war-zone “hospitals” could be, literally, anywhere

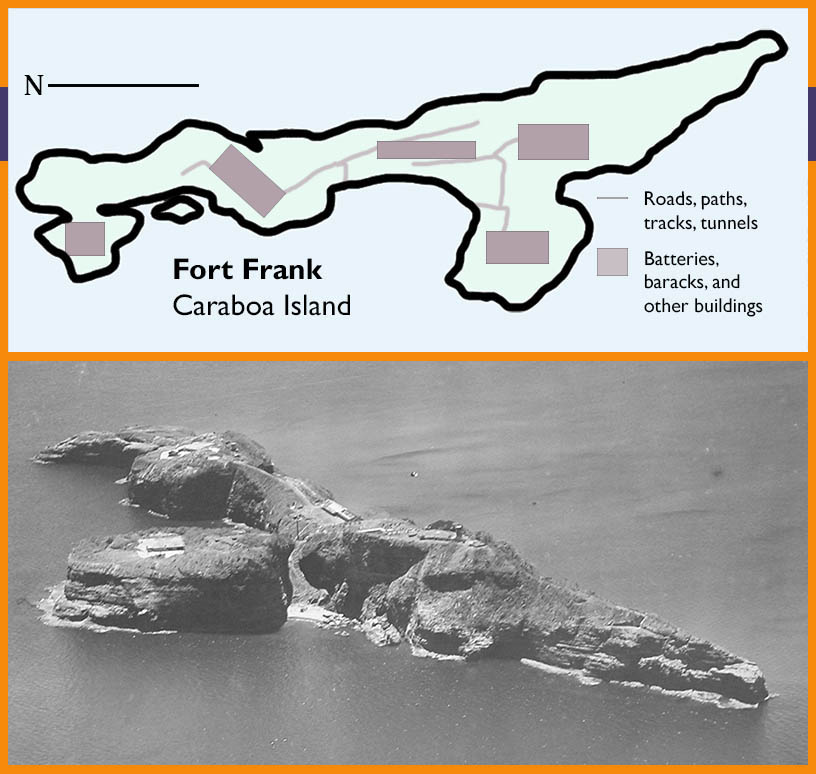

Sitting atop the sheer 100-foot cliffs of Caraboa Island, Fort Frank was one of 4 island fortresses guarding the entrance to Manila Harbor at the outbreak of WW2. Just 44 acres in size and only .5 miles off The Philippine coast, the island was vulnerable to attacks from the air as well as the Philippine mainland.

From January through April 1942, Japanese forces laid siege to Fort Frank and the other 3 sentry islands. Major Goad was stationed on this island during that time.

Fortunately for Major Goad — both as a doctor and a serviceman — the island was not Japan’s main target. So, although the island was bombed and shelled quite frequently, Corregidor island to the north was the enemy’s focus.

Diseases — malaria, dysentery, yellow fever — were likely the biggest health problems at Fort Frank during Goad’s stay. And, ironically, treating diseases led to the fort’s most casualties during the 4 month siege.

On Saturday morning, March 21, 1942, servicemen queued in a Fort Frank tunnel to get Yellow Fever shots. A 240-mm Japanese shell penetrated the tunnels’ 18-inch-thick concrete roof right where the soldiers waited. 28 men died and another 46 wounded in the attack.

4. They practiced medicine as POWs

On May 6, 1942, Japanese forces invaded Corregdior Island, and the Americans officially surrendered the Philippine Islands.

Major Goad was a prisoner of war. Soon he and the other military personnel at Fort Frank relocated to Corregidor Island.

After capture, Lloyd Goad probably worked with other American doctors and nurses in the 1,000-bed, concrete-lined tunnel hospital underneath Corregidor island’s Malinta Hill.

The Corregidor invasion resulted in heavy casualties on both sides, and the Malinta hospital treated ally and enemy servicemen alike. In the first few weeks of captivity, Goad and the other hospital staff saw increasing numbers of men suffering from diseases, dehydration, and malnutrition due to the unsanitary conditions of the POWs’ camp on Corregidor.

Finally, after nearly a month of captivity on the island, Goad and the other American POWs left Corregidor.

5. They served others while enduring brutality themselves

From Corregidor, Goad again entered Manila, only this time as a POW on parade in a Japanese show of military might to the Filipino people.

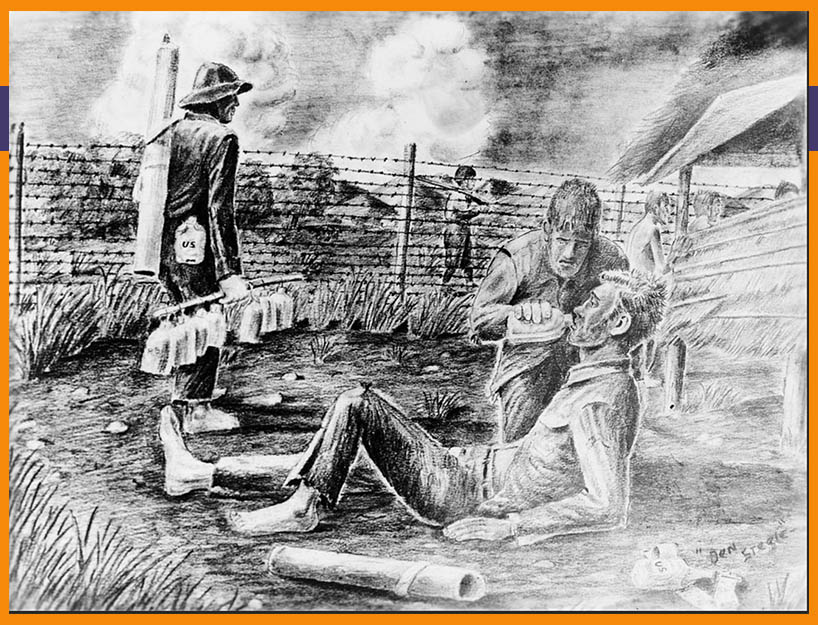

After a night’s rest in Manila, he boarded a cramped, stifling train for a 70-mile journey to Cabanatuan City. The next day brought a 16 mile march to the Cabanatuan POW camp.

The march was brutal, as sick, starving, exhausted POWs trudged along a dirt road, up hills and down, under the relentless Philippine sun.

Many dropped along the way.

“I suffered a complete blackout from heat [exhaustion],” recalled Lt. Commander Alma Salm, one of those struggling POWs and my great-grandfather. “I recovered consciousness with Captain [Lloyd H.] Goad, Army Medical Officer, kneeling by my side.”

The other POWs continued toward camp, but Goad stayed behind to help Salm. That in and of itself was a risky move, as the guards often showed little compassion for fallen POWs and those who tried to help them.

“He had a small pocket medical kit,” Salm continued, “and revived me with some preparation he administered.”

A half hour later, a truck picked up the fallen POWs, including Salm and Goad, and took them to Cabanatuan POW Camp #3. There they rested in the shade of a small tree and waited for the marching POWs to arrive.

6. They established POW hospitals at prison camps

At first, Cabanatuan had 3 POW camps, all of them overseen by the same Japanese commander. Major Goad initially went to Camp #3.

He and the other medical POWs faced a daunting task at Cabanatuan — stemming the tide of disease and malnutrition that plagued the camp’s occupants. With insufficient drinking water, disease-carrying insects, and horrifically insanitary latrines, conditions were ripe for serious health problems.

Then the Bataan Death March survivors arrived, and Goad and the other Corregidor POWs would have realized just how lucky they had been.

“Along the road came a ragged formation of dirty, unkempt, unshaven, half-naked forms, pale, bloated, lifeless,” recalled Cabantuan’s medical director. “Limbs grotesquely swollen to double their normal size. Barefeet [sic] on the stony road. . . . Some stark naked. Bloodshot eyes and cracked lips. Smeared with excreta from their bowels.”

Goad and other medical personnel established a camp hospital, where they treated the diseased, starving, malnourished POWs.

1,287 American POWs died at the 3 Cabanatuan POW camps during June and July 1942, the camps’ first 2 months of operation. The camp hospital’s first death-free day wouldn’t come until December.

Major Goad would have been in the middle of all the sickness and death.

7. They had it (somewhat) than other POWs

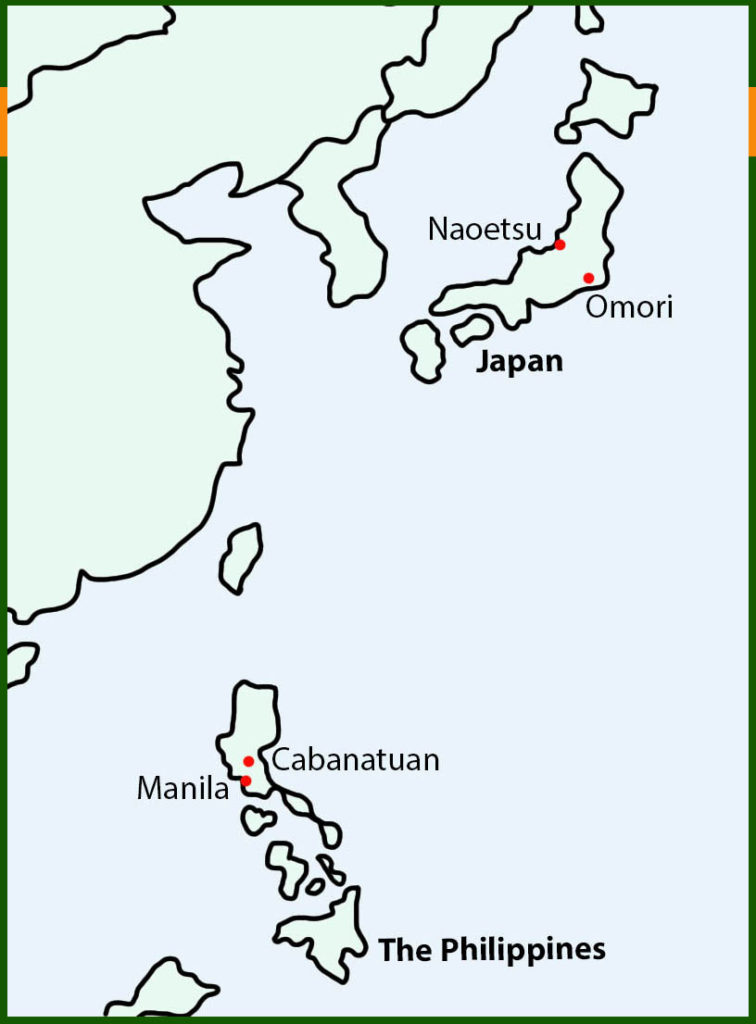

At some point, likely in summer or fall 1944, Major Goad was transferred to the Japan mainland.

Goad spent time at the Naoetsu POW Camp, made famous by the book and movie Unbroken detailing Olympic sprinter Louis Zamperini‘s POW experiences. Everyday, the malnourished, exhausted Naoetsu POWs marched 1 mile (each way) to slog through work at a local steel mill. But Lloyd Goad was probably spared the hard labor, instead working in a medical capacity .

He later transferred across the island to Omori POW camp near Tokyo. This camp sat on a small, man-made island built by POWs. Interestingly, Louis Zamperini also was a prisoner at this camp, although I don’t know if their stays overlapped.

Another individual at both the Naoetsu and Omori POW camps was Mutsuhiro Watanabe, a Japanese guard nicknamed “The Bird.”

The Bird was known for brutality. “I treated the prisoners strictly as enemies of Japan,” Watanabe later recalled of his war-time actions. Post-war he was number 23 on General MacArthur’s list of top 40 war criminals, although the guard was never captured or punished.

“My thoughts were of Watanabe and what would happen if I ever met him again,” Lloyd Goad wrote 44 years after his release. “Not pleasant thoughts for years to come.”

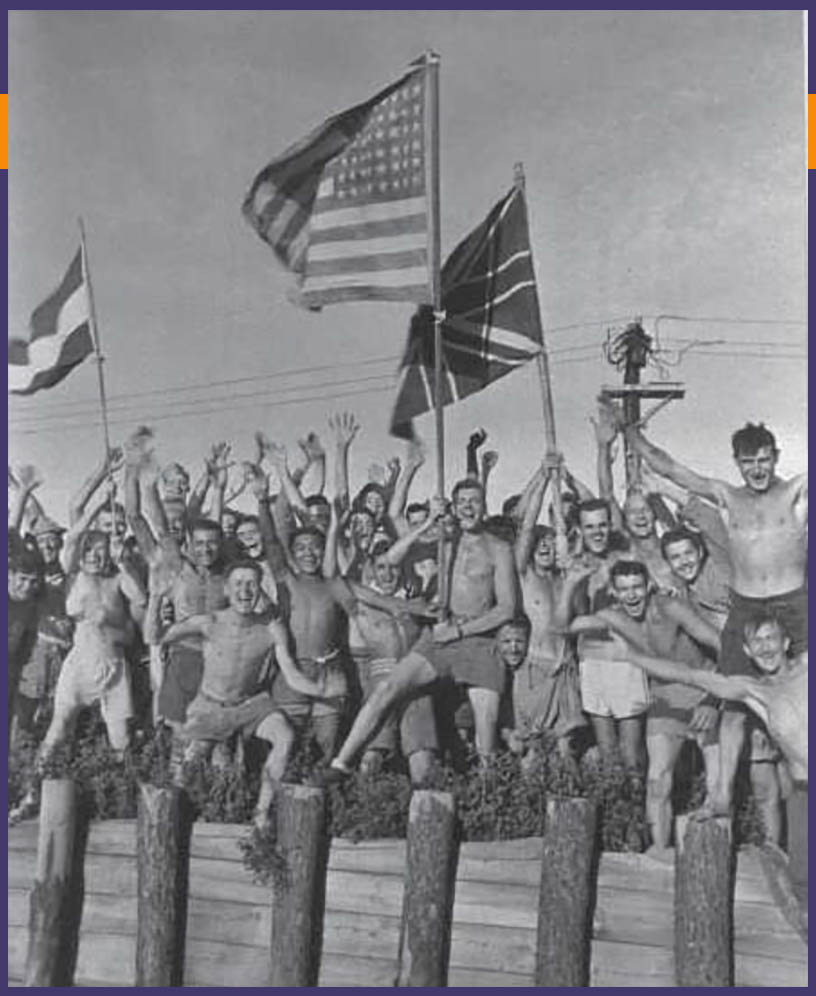

American forces liberated Major Goad and his fellow Omori prisoners in September 1945.

He’d survived 5 months in war-zone hospitals and 40 months as a POW.

I once met a WW2 medic veteran who told me about working on “the boys” liberated from Japanese camps. He recalled, still revolted, the awful physical condition these men were in. Dr Lloyd Goad treated these kinds of cases, and worse, for some 4 years. It must have been indescribably horrific.

8. They often left the military behind

Lloyd Goad married Lois Otto in January 1948. The couple soon moved to Golden, Colorado, where Lloyd began practicing medicine. He eventually partnered with his son (a 3rd-generation Goad-family doctor).

Lois and Lloyd raised 3 sons and 1 daughter in Golden, then remained there after he retired in 1980. In 1989, Lloyd wrote a memoir of his POW experiences called “A Guest of the Emperor: Before, During, After.”

Lloyd Henry Goad died on March 19, 2002. He was 88 years old.

He rests in the Golden Cemetery in his adopted hometown in Colorado.

Read Next

Sources

- Alma Salm, Luzon Holiday, memoir, manuscript, possession of Anastasia Harman, online at “Exposed: A Lesser-known WW2 Death March, AnastasiaHarman.com, https://www.anastasiaharman.com/2020/02/28/lesser-known-death-march/.

- “Attack on Clark Field,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Clark_Field, accessed 12 June 2020.

- “Fort Frank,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Frank, accessed 12 June 2020.

- J H Goad family, 1920 US Federal Census. Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Original data: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Accessed June 12 2020.

- James H Goad family, 1930 US Federal Census, Gary, Lake, Indiana; Page: 27B; Enumeration District: 0044; FHL microfilm: 2340334. Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- John Schriver, review of Lloyd H Goad, “A guest of the emperor: Before, during, after,” Amazon.com, found online at https://www.amazon.com/guest-emperor-Before-during-after/dp/B0007C3HEC, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Goad’s memorial page, Find A Grave, online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/57024490, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Goad, 1931 Mann High School Yearbook, Gary, Indiana, page 39, Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed 22 June 2020.

- Lloyd Goad entry, Ancestry.com. U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Lloyd A Goad entry, Iowa, Births and Christenings Index, 1800-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd H Goad entry. Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of the Japanese File, 2007 Update, 1941-1945. ARC ID: 2123836. National Archives at College Park. College Park, Maryland, U.S.A. World War II Prisoners of the Japanese Data Files, 4/2005 – 10/2007. ARC ID: 731002. National Archives at College Park. College Park, Maryland, U.S.A. Records of the Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, Collection ADBC. ARC: 718969. National Archives at College Park. College Park, Maryland, U.S.A.

- Lloyd H Goad. Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

- Lloyd Henry Goad, Ancestry.com. U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for Indiana, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 282. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Henry Goad MD entry, Ancestry.com. Iowa, Marriage Records, 1880-1951 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. State Historical Society of Iowa; Des Moines, Iowa; Series Title: Iowa Marriage Records,1941-1943; Record Type: Marriage. Iowa Department of Public Health. Iowa Marriage Records, 1880–1951. Textual Records. State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Henry Goad obituary, Denver Post, The (Colorado), 29 March 2002, found online at GenealogyBank.com https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/0F97FB7F4AF45685-0F97FB7F4AF45685), accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Henry Goad obit, Rocky Mountain News (Colorado), 26 March 2002, found online at GenealogyBank.com https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/0FE15592B45FDEE4-0FE15592B45FDEE4, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Lloyd Henry Goad. Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Social Security Applications and Claims, 1936-2007. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Maj Joe C. East, March 21st Fort Frank Shelling, a 2-page typescript in OCMH, cited in “The Siege of Corregidor,” Louis Morton, The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, US Army, 1953, page 487, found online at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_27.htm, accessed 22 June 2020.

- Mary Ellen Condon-Rall and Albert E. Cowdery, “A Medical Calamity,” in The Medical Department: Medical Service in the War against Japan, Center of Military History, US Army, Washington, DC, 1998, p. 23-24, found online at https://history.army.mil/html/books/010/10-24/CMH_Pub_10-24-1.pdf, accessed 12 June 2020.

- “Mutsuhiro Watanabe,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutsuhiro_Watanabe, accessed 12 June 2020.

- “Naoetsu POW Camp Tokyo Branch Camp,” http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/tokyo/tokyo_4_naoetsu/tok-04B-Naoetsu.html, accessed 12 June 2020.

- “Omori, Tokyo Camp,” found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/tokyo/omori/omori.html, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Ricardo T. Jose, summary of Lloyd H Goad, “A guest of the emperor: Before, during, after,” Filipinas Heritage Library, found online at https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/61354/, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Rose E Goad family, 1940 US Federal Census, Gary, Lake, Indiana; Roll: m-t0627-01120; Page: 15A; Enumeration District: 95-32B. Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. T627, 4,643 rolls. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- “Sternberg General Hospital,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sternberg_General_Hospital, accessed 12 June 2020.

Images

- Image 1. Sternberg Hospital. Found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/344947652682667926/, accessed 22 June 2020.

- Image 2. Lloyd Goad yearbook photo. 1931 Mann High School Yearbook, Gary, Indiana, page 39, Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed 22 June 2020.

- Image 3. Map of Manila Bay. Created by Anastasia Harman, 2019.

- Image 4a. Ft Frank Map. Map created by Anastasia Harman, June 2020.

- Image 4b. Aerial view of Caraboa Island ca 1923, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) image, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/44567569@N00/30380121831/in/album-72157673964028162/, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Image 5. Malinta Hospital after capture. Found online at John Moffitt, “The Malinta Tunnel, from Concept to Completion,” Dec 2012, Rediscovering Corregidor, http://corregidor.org/fieldnotes/htm/fots2-121224-2.htm, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 6. Philippine countryside. Adobe Stock Photo image, licensed by Anastasia Harman 2019.

- Image 7. Cabanatuan POW drawing. By Ben Steele, found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/93660867222677847/?lp=true, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 8. Map of Japan POW Camps. Created By Anastasia Harman, June 2020.

- Image 9. Mutsuhiro Watanabe. Image found in numerous online locations, including Wikicommons.

- Image 10. Cheering Omori POWs. “Omori, Tokyo Camp,” found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/tokyo/omori/omori.html, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Image 11. Pic of Lloyd Goad. Uploaded by D_Bone192 to Ancestry.com, 10 February 2017, online at https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/164360489/person/112139537672/media/ba8d403a-dc18-4268-b8ed-dc0f5bef86db?_phsrc=gPb3624&usePUBJs=true, accessed 9 June 2020.

- Image 12. Grave site. Images uploaded by Scotti McCarthy to Lloyd Goad’s memorial page, Find A Grave, online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/57024490, accessed 12 June 2020.