This post contains some graphic, war-related content.

As we moved slowly across Manila Bay, eastward, heading into the inevitable blistering sun, my thoughts turned back to recent duty on board the American submarine tender, the “USS Canopus.”

Although attached to the tender only a short time before hostilities commenced, I held fondest memories of the “old floating apartment house” dating back to the late “twenties” — at which time I had been attached to her for over two years in Philippine and Chinese waters.

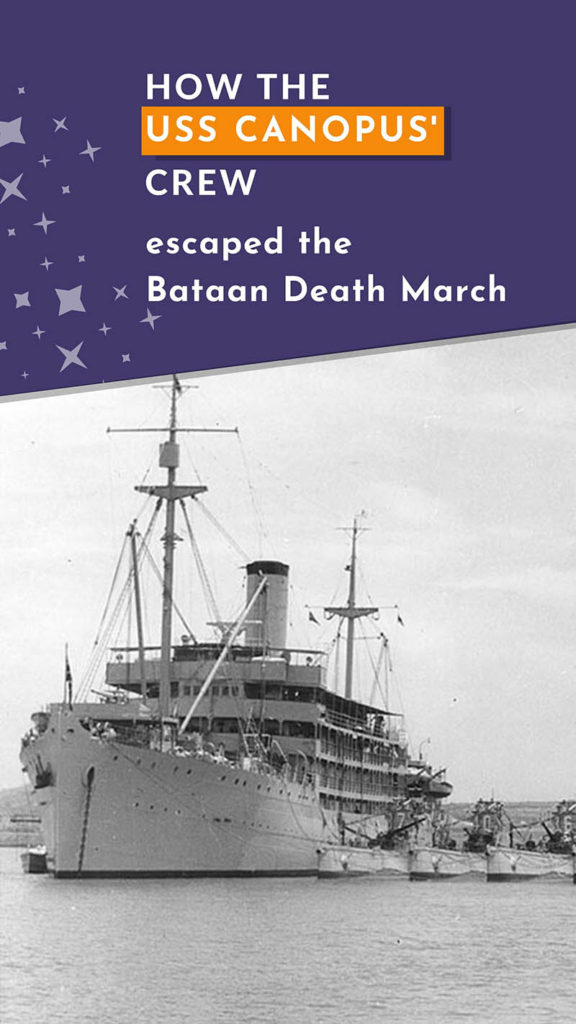

The USS Canopus was an old submarine tender whose sole duty was to mother her brood of “pig boats.” From her the subs obtained their provisions, lubricating and fuel oils, and equipment and the performance of necessary repair work with which to keep that deadly undersea engine of war in the highest of material efficiency.

This vessel was under the able command of Captain E. L. Sackett, US Navy, an old submariner whose inspiring leadership was responsible for the high morale of those under his command.

Fleeing the Japanese attack on Manila

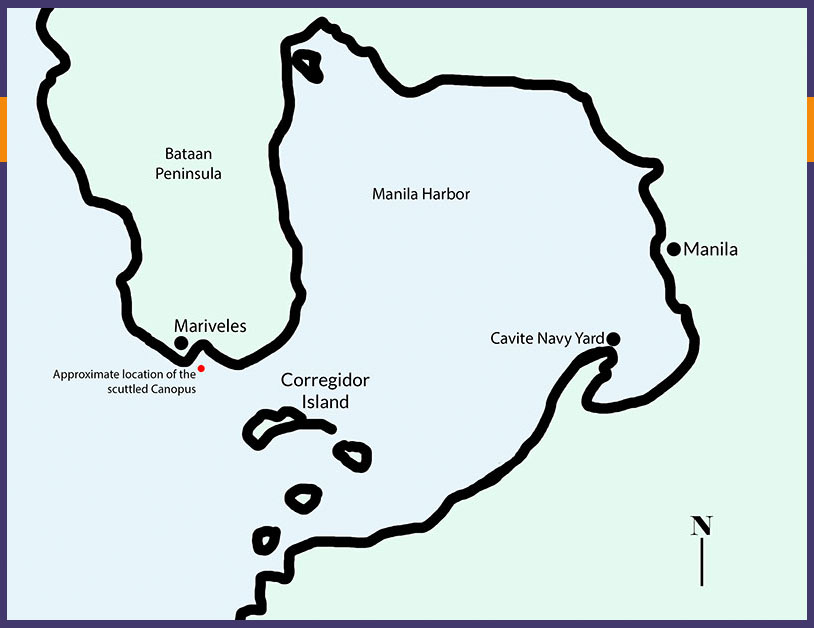

The Canopus, camouflaged with paint and large fish nets [so that Japanese planes wouldn’t bomb it], was moored alongside the dock between piers three and five in Manila prior to Christmas Day 1941. From that point, we who were attached to her, could see the burning of the U.S. Naval Station at Cavite, nine miles away across the southwest corner of Manila Bay.

My storekeepers — Arthur Lazcano, William Patton, Gordon Fontaine, with John Burk as senior — were left in charge of the Navy bodegas (warehouses).

Storekeeper Arthur Lazcano

Storekeeper Gordon Fontaine

They had been rushing around Manila trying to unearth and procure much needed supplies of various kinds as well as the very important items of oxygen, acetylene, and the very precious Freon compressed gasses — the latter so essential for submarine refrigeration and air conditioning on those undersea boats.

Manila was declared an open city [on December 26, 1941], so we had to “weigh anchor” that night. I left word with Loscano to continue their efforts and to procure as many stores as possible and with added instructions, “Take care of yourselves, and, for God’s sake, don’t let the Japs get any of those submarine stores stowed in the bodegas,” then I bid them a hurried goodbye. It was almost two years before I saw them again.

We silently moved down the bay [Manila Harbor] in a total blackout and under the protecting anti-aircraft guns of Corregidor, anchored at Mariveles Harbor just outside of Manila Bay.

Here we further camouflaged the vessel with paint to match the vegetation on shore, plus securing tree branches and other green foliage to the masts, spars and rigging, and superstructure to obscure our presence from the enemy searchers in the air.

A close call in Mariveles Harbor

During the lull between enemy air fights, I was directed to put out in a small Navy motorboat and chart the location of the various oil barges and lighters in Mariveles Harbor and determine their contents. We were looking for additional quantities of diesel oil which was especially precious to us at this time.

Editor’s note: Alma Salm was the Supply Officer for the Canopus. He and his Storekeepers (mentioned above) were responsible for procuring enough supplies — such as diesel oil and gasoline — for the ship, its personnel, and the submarines they tended.

While engaged in this survey, five Jap dive bombers swooped down over us from the hills on the western side near its entrance. We stopped the boat and “lay to” while adjusting life jackets and putting on steel helmets of [World] War I vintage, expecting the worst.

However, the enemy was after “bigger fish.” They passed over us at three thousand feet, went into a dive and dropped their “stick of bombs” midst a group of larger Naval craft a short distance east around the point.

Evading the Japanese in Bataan’s jungle

My next problem was to procure for naval uses more gasoline, which was under the jurisdiction of the Army. The greater portion of the Navy’s gasoline caches had been destroyed by Jap bomb hits. The Army permitted us to use from their supply which was cached in ditches near the roads all over the southern end of Bataan Peninsula and concealed from aloft with vegetation.

This area had not become so “hot” [ie, the Japanese weren’t dropping as many bombs in that area] as the Jap infiltrationists had finally succeeded in landing behind our lines from the sea but only after suffering heavy casualties to both personnel as well as to material. This became a problem, and they were a menace for a time.

A Naval Battalion under the command of Commander Francis Bridget, with the help of Lt. Commander Henry P. Goodall and his men from the Canopus attacking from the sea, had been able to localize these infiltration and inflict effective blows against these “stab in the back” Jap soldiers who were especially seasoned for this type of fighting.

With a truck we penetrated eight kilometers back thru the jungle to the gasoline storage cache in an open area — a bulge in the road.

We felt as though we’d been dropped into a “goldfish bowl,” for all the natural protection it offered. This was the outer perimeter of the infiltration area. My men hurriedly loaded the heavy drums of gasoline while four of us “on the alert” trained our guns on the dense thicket watching for any suspicious movements.

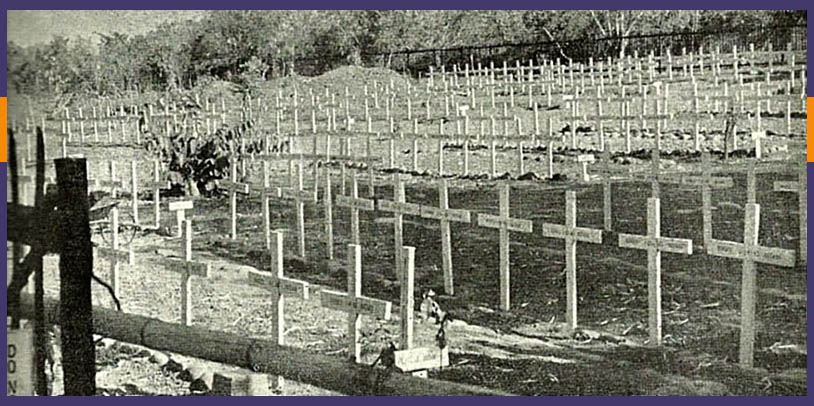

A short time before, less than two hundred yards from us near a small cemetery which had been established only recently and that contained the new graves of thirty or forty of our soldier dead, an Army sentry, patrolling against this menace, was cut almost in two by a burst of machine gun fire from an unseen Jap infiltrationist.

When we finally arrived back with our highly prized cargo intact, I honestly admit, I had a pretty good case of the “runs.”

Sinking of the USS Canopus — an early WW2 ship casualty

Is wasn’t long after our arrival in Mariveles before a Jap armor-piercing bomb struck the after-well deck of the “old tub.” Penetrating to the engine room, it injured Warrant Machinist Adolphus C. Hutchinson, badly burned Warrant Electrician Alton Hall, and killed several of the crew.

Although many attempts were made to destroy the battered old boat that had served so long, with bombs literally rained down, yet she sustained only two direct hits. She remained afloat until the capitulation of our forces on Bataan, when we had to scuttle [ie, deliberately sink] her to keep her from falling into Jap hands.

Escaping the Bataan Death March by mere hours

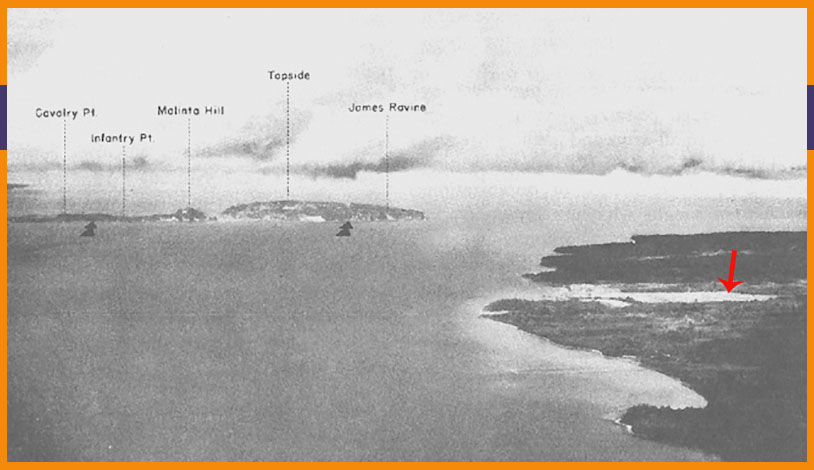

Word came from Corregidor at the eleventh hour [probably late on April 8 or early on April 9, 1942] that our Naval unit would be permitted on the “Rock.”

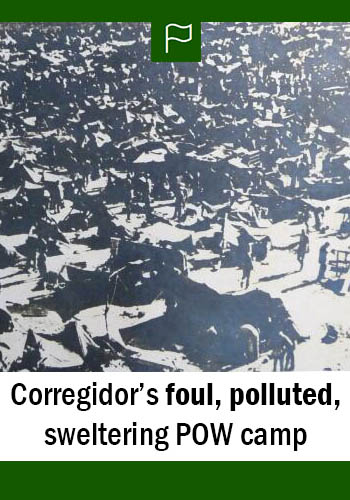

Editor’s Note: This means that the crew of the Canopus would be allowed on to US military base on Corregidor island instead of having to surrender to and become POWs of the Japanese. This decision spared Salm and the other Canopus crew the horrors of the Bataan Death March. However, the majority of the Canopus crew became POWs a month later.

We worked furiously most of the night to load the lighter boats with miscellaneous stores and small equipment to take with us after learning that the fall of Bataan was imminent and our forces perhaps would not be able to hold out until morning.

Staying ahead of the Japanese advance

Our motor launch was the last to leave the ship [before it was scuttled].

We headed toward the small angle dock a thousand yards up the east side of the harbor to pick up the last of the navy demolition squads who had been busy meantime in blowing up our storage tunnels on shore.

The scene reminded me of a gigantic Fourth of July celebration back home.

Our troops beyond the ridges were destroying all ammunition and supplies in the wake of the fast moving Jap advance. The result was not only the almost continuous thunderous detonations but a huge conflagration which illuminated the surrounding country.

This, together with gigantic explosions from the heavy dynamite charges in the string of tunnels, filled the air with heavy acrid fumes and smoke which lay like a pall over the placid waters of the bay.

The little light from a waning moon gave it all a very eerie appearance.

A traumatic goodbye

Suddenly the whole hillside in front of us erupted in a tremendous explosion that was so great it almost tore us loose from the boats.

A great number of drums of gasoline had been stored in a tunnel ashore. When the entrance was dynamited and sealed, apparently the fire set off the gasoline. This caused a gigantic explosive charge to form.

The upheaval took place directly in front of us about two hundred yards away. In addition to the mighty concussion, it hurled huge boulders directly into the harbor. The calm waters in the immediate vicinity were whipped into turbulence from the fury of it all.

I had been in brief conversation with Warrant Machinist Lynn C. Weeman when the fireworks from the hillside broke loose. This unexpected detonation hurtled massive chunks of rock down through the canopy of the little launch.

I was sitting only three feet from Weeman, but he never spoke again. His head had been practically severed by the falling stone missiles, while I only felt a few small pebbles no larger than peas rain gently on me.

It was with mingled feelings I took this last look towards distant Mariveles Harbor and the last resting place of the Canopus — about eighty feet down in “Davy Jones locker.” I hoped that Japs would not succeed in salvaging her as they had been able to do not infrequently with other sunken vessels.

The sunken treasure of Manila Harbor

Shortly after the war began, we had hidden heavy wooden boxes in Manila Bay containing silver Filipino pesos, reviving an old pirate habit of “buried treasure.” The Japanese, some months later learned of the location of this cache treasure, supposedly from a Japanese mestizo.

It wasn’t long before they had detailed some of our own Naval sea divers to the spot and, from subsequent reports I received from one of the members of that diving detail, they recovered a goodly portion of it.

Read next

Please share

If you think Salm’s memoir is worth passing along to friends or family, we’d love for you to share the link to this post on social media or email. Thank you!

Sources

- “USS Canopus (AS-9),” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Canopus_(AS-9), accessed 19 August 2019.

- “Submarine Tender,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarine_tender, accessed 19 August 2019.

- J. Michael Miller, “Bombing of Cavite,” FROM SHANGHAI TO CORREGIDOR: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines, found online at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003140-00/sec5.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

Images

- Image 1: USS Canopus with submarines. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 2: USS Canopus at Cavite Navy Yard. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-178321, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9-d.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 3: Cavite Navy Yard burning. From the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives, photograph number SC 130991, courtesy of the USNHC, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BurnungCavite1941.jpg, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 4: Manila Harbor map. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 5: Modern-day picture of Mariveles Harbor. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 6: Mariveles Harbor. From Louis Morton, “Japanese Plans and American Defenses,” The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1953, found online at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_29.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 7: Bataan landscape with Mt. Mariveles. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 8: Mariveles cemetery. Japanese Philippine Expeditionary Force photo from the book Philippine Expeditionary Force, 1943, Manila, found online at http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/819/navy-tunnels-exist-mariveles-2010?page=2, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 9: Portrait of Lynn C Weeman. Found online at “Mach Lynn C Weeman Memorial,” photo added by Sandra Knapp Smith, Find -a-Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56774368, accessed 20 August 2019.

Thank you for this information, my Father ” John R. Christian TM3 ” was part of the crew of the Canopus. I had received my middle name after one of his fellow TM shipmates, TM3 Singletary.

My Father was finally released at the end of the war in Sept. 1945 but, killed in an auto accident by a drunk driver in Oct. 1965

John, Thank you for commenting! I LOVE connecting with people who have connections to the Canopus. I just looked up your father in my POW databases, and he was captured on Corregidor island. My guess is he spent time in Cabanatuan POW Camp (with all the other Corregidor POWs) before being transferred to the Tokyo POW Camp Branch #2 (Kawasaki) where he was released in September 1945. Here’s a link to some information about that camp, if you’re interested: http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/tokyo/kawa2b/kawa-2b.htm Looks like the camp was attacked by Allied bombers at one point while the POWs were there. Terrifying. Thank you for reaching out!

My father EM2C Bennie Krupa, served onboard the Canopus. He ended up as a POW for 42 months. He would not speek of his experience for at least 50 years. This story is almost word for word the story that he “finally” told me when he started talking about it when he was 85 years old. He told how they would camophalage the ship and hid their stores. How the Japanese plane dropped one bomb, But it hit in the right place, how the ship was scuttled. He was injured from the explosion of the mountain storage caves,. He was Held in Toroku POW camp. It must have been Hell, because it took him so many years to finally be able to even talk about it. I am sure there was much he held back on.

Thank you for sharing your dad’s story. It’s good that he was finally able to talk to you about his experiences. He probably experienced another unimaginable experience on the transport ship to Japan. Those ships are often called Hell Ships. They were awful.

Thank you for posting Mr. Salm’s memories of the USS Canopus and also links to his other writings. My father was stationed on the Canopus but never talked much about it. Only after he passed and I obtained his Naval service records that I discovered he was transferred off the ship (to another sub tender-USS Otus) shortly before the fall of the Philippines. Perhaps he felt some guilt, but I will never know.

On a brighter note, I am glad to see you are keeping these memories alive!

Hi Rick, Thank you for reaching out and sharing a bit about your father. I suspect your father and Mr Salm (my great-grandfather) would have known each other. Salm, as I understand it, was the officer in charge of handing out Canopus paychecks — so it’s likely they came in contact with each other. It’s So important to me to keep these memories alive. This story and these men are slipping too far from our collective memories, and I want to make sure that doesn’t happen. Thanks for being part of the journey!

Anastasia- I wrote a comment last week but I guess it didn’t go through. I’m researching my wife’s Uncle; Robert Lewis, GM3, who was a shipmate of your great grandfather on the Canopus. He died July 4, 1945, in Japan after laboring at the Osaka Main Camp-Chikko. He was placed in Kobe POW hospital on May 22, 1945, with TB, plus he was badly burned when the hospital was bombed by our B-29s on June 5, 1945. I have been able to learn much about his last month and a half, but not so much about his time in the Philippines. He was originally assigned to the USS Permit, one of the subs assigned to the Canopus, but for a reason unknown to us he was re-assigned to the Canopus. Irony is, if he had remained on the submarine he would have likely survived the war. The book I am currently reading is “Ghosts of Canopus – The War Diary of a Lucky Old Lady.” I presume you have read it? What I don’t know is whether Gunners Mate Lewis made it to Corregidor as your Great Grandfather did, or was he part of the Canopus crew who went and stayed ashore with the Marines on Bataan, and therefore had to survive the Bataan Death March. I’d also be interested in knowing what POW camp(s) he was at in the Philippines and what hell ship he was on for transport to Japan. What a truly amazing generation, as my father was in the Army in the European theater. Thanks.